Cat haul trucks have moved more than 6 billion metric tons autonomously and 620 Cat haul trucks are

currently operating autonomously 24/7 on three continents. (Photo: Caterpillar)

Autonomous Operations Reshape

Open-pit Mining

The keys to success lie in understanding fleet strategy and training managers

to properly execute the plan

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

All the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) for haul trucks have AHS platforms and several companies have developed independent systems. To implement AHS, mining engineers and operations managers must not only accurately assess their current capabilities and their fleet, but also understand what direction the company might take in the future and how that will affect the fleet. Will the mine be automating the truck fleet only or will it apply automation as much as possible, including ancillary equipment and light duty vehicles? Some countries have mandated or are considering certain safety protocols such as collision avoidance systems (CAS). How will that factor into the decision- making process?

Then there is the move toward decarbonization to reduce the mining industry’s reliance on diesel fuel. Whether the mine opts for trolleys, battery- electric, hydrogen or some hybrid form of propulsion, it’s becoming more evident that autonomous operations will be needed to make that transition.

The mining industry has gained a lot of experience with AHS in a relatively short period of time and that knowledge base continues to grow. So much so, that AHS can be scaled down economically for smaller fleets and smaller operations including large quarries. Experience has also taught the industry that successful implementation requires patience and persistence, and the support and understanding of the managers who will be installing and maintaining the systems.

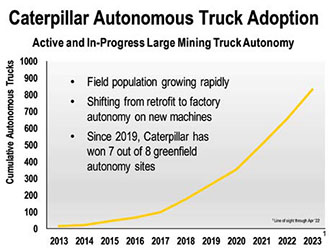

Cat Sees More Mines

Moving to AHS

Cat haul trucks have moved more than

6 billion metric tons (mt) autonomously

and they have 625 haul trucks operating

autonomously 24/7 on three continents.

Autonomy is a topic of conversation

in nearly every customer meeting

that we have today, said Denise Johnson,

group president for Caterpillar Resource

Industries. “Beyond answering

questions about the technology and

digital solutions, we often find ourselves

explaining how autonomous

operations can not only enhance the

machine’s useful life, but also how it

can really improve site safety and productivity,”

she said. “We’re converting

existing mines and equipping greenfield

sites. Greenfield mines can be

designed specifically for autonomous

operations from inception and those

conversations usually begin when the

operation is in the permitting phase.”

Caterpillar has been involved from day one with several greenfield operations, including Anglo American’s Quellaveco copper mine in Peru, Teck’s Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 copper mine in Chile, Rio Tinto’s Gudai-Darri iron ore operation in Western Australia, and IAMGOLD’s Côté mine in Ontario, Canada. Newmont converted its fleet of haul trucks to AHS at the Boddington gold mine in Australia. Recently, Freeport-Mc- MoRan announced its plans to work with Caterpillar on converting its fleet at the Bagdad mine in Arizona, USA, to AHS.

Consistency is another key benefit. AHS requires no breaks or shift changes, and really no need to stop unless another piece of equipment enters the same intersection, or the truck needs to refuel or visit the shop for maintenance. “Once AHS is implemented the mines can continually improve, pulling out every bit of waste, making the processes more repeatable like a factory,” Johnson said. “Autonomy really provides 100% process conformance.” Some of Caterpillar’s customers are reporting productivity improvements as high as 30% with autonomous operations.

When Caterpillar started deploying autonomy, it started with large mines with 70 or more haul trucks. With time and experience, the company is now able to apply those same economics for mines operating as few as 12 haul trucks. “We are currently developing a new autonomy platform that will scale modularly down to small fleets,” Johnson said. “A quarry application that may only have three or four trucks and a few loading tools would be able to leverage that as well. That will really unlock the capability of autonomy.”

Cat MineStar Command for hauling is enabling this transition to autonomous operations. The advantage with Cat equipment is that the technology is integrated into the machine. With all of the sensor information that is available now, the mine can not only see how efficiently the individual machines are working, it can also look at optimization across the entire site. “In the near future, we will be able to leverage this integration with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, which will take us to the next level from an improvement perspective,” Johnson said.

Cat’s MineStar Command can also run mixed fleets. “We recognize that a lot of mines have mixed fleets,” Johnson said. “While we would love to have everyone operating Cat machines, Mine- Star Command allows us to integrate our solution with that mixed fleet. That ability is what has made us so successful. It allows miners to improve safety, be more productive, and lower their costs.”

Autonomous operations will also assist as mines move toward decarbonization. Whether it’s connecting a pantograph to an overhead trolley line or positioning the machine to recharge its batteries, electrified fleets will benefit from precise operations. “When you think about the complexity of charging the batteries for a fleet of 40 haul trucks while operating 24/7, it will be very difficult to maintain productivity levels without autonomy,” Johnson said. “The decisions around the state of the charge versus productivity, for example, will be too difficult for people to manage. When planning the mines of the future, it’s clear to see the power of the digital tools that will be needed for decision-making, optimization, and simulation. We’re investing a lot in digital technology to unlock that potential.”

Over the last 20 years, Caterpillar has invested about $30 billion in autonomous solutions. “The mines provide us with feedback as far as further improvements,” Johnson said. “We leverage that feedback with the new technology coming from our R&D center to decide on the next use case, or the next features that we will add to the autonomous layer. Quite a bit of investment is going into that new autonomy platform that we will be standing up soon.”

Caterpillar is also engaged with the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) and its Innovation for Cleaner, Safer Vehicles (ICSV), which is an initiative that brings its members together with many of the world’s largest OEMs, in a non-competitive space to accelerate the development of a new generation of mining vehicles and to improve existing ones.

“Caterpillar is involved with a number of ICSV work streams within that innovation environment,” Johnson said. “One is around ensuring that collision avoidance is something that is optimized across the industry. ICMM will roll that out as a standardized interface, and we’re participating in that with several other mining companies as well as other OEMs. We will have a CAS in development that will be deployed shortly.”

Johnson believes that at some point, every single piece of equipment on a mine site will be automated in some way. “We started with trucks because that made the most sense from a productivity perspective,” she said. “We’re leveraging the technology with drills, water trucks and dozers now. As far as underground mining, autonomous operations are well established. Surface loading tools, shovels and excavators, will be the last, but we’re already looking at automated assist features for those loading tools.”

When it comes to autonomous operations for open-pit mining, Johnson said she is most excited about the continuous improvement trajectory and the ability to improve that trajectory with tools like machine learning and AI decision making. “This will unlock capabilities that we have never had before and it will allow us to think about the mining process much more holistically,” she said. “At the end of the day, these solutions are there to help improve safety and lower the cost for mining operations. By improving productivity, they achieve better results with less work and waste.”

Understanding the Fleet

Strategy

Miners in Western Australia have a

deep understanding of the value of

AHS, said Drew Larsen, director of

business development for ASI Mining.

“With the concentration of AHS deployments

in that region, there is a great

deal of collective experience with autonomous

operations and how it can

help increase productivity and reduce

mining costs” he said. “Adoption rates

are growing in other markets, but a lot

of precedents have been set in Western

Australian iron ore.”

When mining companies are considering AHS, Larsen said one of the biggest challenges is understanding their fleet strategy. “If the mine is currently running a mixed fleet, they’re faced with the prospect of having to replace a portion of the fleet well before end of its useful life to adopt a particular autonomous platform,” Larsen said. “With ASI Mining, they can continue to run the existing fleet.” Beyond that, mine operators might be facing other decisions regarding the future of their haul truck fleets. “Is decarbonization a consideration?” he asked. “Are they going to be leveraging battery-electric? Are they going with hybrids? Are they considering smaller trucks? What will emerge over time? There is still enough murkiness that it is important to have the maximum flexibility with future fleet strategies. That flexibility would also extend to incorporating a mix of ultra class trucks with smaller trucks, new trucks with older trucks, and mixed fleets of different makes and models.”

Autonomous operations require a level of operational rigor and discipline that are not always well-established today, Larsen explained. “It takes a significant amount of work to successfully roll out and maintain an AHS platform that yields the results that autonomy is capable of providing,” Larsen said. “Some organizations are better equipped to do that than others. On the change management side in particular, it requires a high level of human capital. How well the organizations can deal with all the human factors during and after the rollout plays a large factor in the success of the program.”

All mine operators should be considering a roadmap which factors the potential benefits of autonomous systems. Some regions, such as South Africa, have seen mandates for solutions such as Collision Avoidance Systems (CAS) for mining equipment. Other regions, including the USA, are considering similar mandates. These decisions certainly drive a level of technology deployment, Larsen explained. “With CAS, the mine would already be fitting the machines with sophisticated hardware and software that starts to overlap with the hardware and software needed to do a full autonomous conversion,” he said. “In that example, CAS systems could become a steppingstone into a full autonomous capability, particularly on haul trucks.”

If a mine incurs the cost to roll out a CAS system based on a safety case, the return, of course, is improved safety. “If the mine rolls out an AHS, it gets the benefits of CAS, along with all the upside of the increased utilization of truck availability and other benefits associated with autonomy,” Larsen said. “Rather than potentially incurring regret spend by deploying CAS, which then may become partially obsolete with AHS, strategic planning should consider if it makes more sense to go straight to autonomy. These are some of the considerations mine operators should take in road map planning.”

Larsen said ASI Mining has focused its R&D efforts on improving the robustness of AHS around availability and efficiency. That also relates to infrastructure dependencies such as communication networks, servers, GPS, road conditions, and other factors that impact overall AHS performance. “There are cases where that infrastructure can be impaired, especially with deeper pits,” Larsen said. “We are working on ways to mitigate those issues along with some of the other environmental situations that historically have impacted the efficiency of AHS.”

“We also have this convergence of the push for autonomy and decarbonization and there is a lot of relevance between the two,” Larsen said. “The decarbonization solutions being discussed today, whether it’s trolleys, battery-electric or other hybrid technologies, will require the precision and repeatability of an autonomous system to achieve optimal results.”

“For example, with trolleys, the mines will need to consistently position truck pantograph optimally under the overhead cable and make dynamic decisions which consider load factors and other parameters. With the variability that’s introduced by manned operations, those aspects become much more difficult” Larsen said. “The same is true with battery-electric systems. The mine will face more decisions in terms of optimum routing and energy management, which will impact the mine plans.

“We’re also starting to see some of the old paradigms challenged around big trucks versus small trucks,” Larsen said. “Autonomy opens a lot of new ground for that debate. Can a combination of large and small trucks be used more effectively as the mine works different parts of the pit? Certain trucks are better suited for difficult conditions than others. Getting all of them to work together under a common control system may become increasingly important.”

Autonomous operations can also influence mine design. Larsen said he believes there is a lot of runway available to really unleash some of the more radical or more extreme cases where mine design can really be impacted by leveraging of autonomy. “I don’t think the industry has fully realized that potential yet,” Larsen said.

With autonomous operations, the industry is heavily focused on haulage, but ASI Mining sees more broad applications. “We see an opportunity to really flesh out an OEM agnostic capability that spans across more than just haulage,” Larsen said. “We have Mobius for Drills, which Epiroc currently offers with all new surface drills. Additionally, ASI Mining offers capabilities for semi-autonomous blasting, using its Mobius for Blasting applications. Other autonomous and semi-autonomous applications that leverage Mobius are also on our roadmap.”

AHS and the Valley

of Despair

According to Craig Gillespie, founder

and CEO of Absolute Autonomous, the

Valley of Despair occurs when a project

or an initiative, generally a big change

around technology, produces less than

ideal results, which leaves employees

feeling frustrated and discouraged over

the learning curve. “They generally lose

enthusiasm before they have given the

new system a chance to truly prove itself

and understand what it can do,” Gillespie

said. “Mining professionals experience

this many times when implementing

AHS technology. The initial excitement

can quickly turn into frustration.”

After working with multiple AHS implementations over the years, Gillespie cites three factors that cause the Valley of Despair: inadequate plans and processes, lack of advanced skills and knowledge around the new technology, and a failure to understand open communications around the change. “The good news is that I’ve also seen teams work together to implement what is required to help miners climb out of the valley before they get stuck,” Gillespie said.

A valley can only exist between two peaks, Gillespie explained, and while it’s a steep decline from the top to the valley floor, the ascent can be just as steep with the proper processes in place, along with training and encouragement from management. “Once they reach that peak, that’s an invigorating feeling for them and one that my colleagues and I have seen many times before,” Gillespie said. “That’s how working through a big change like AHS can go for your team. They need to understand the processes, what is required of them, the required skills and knowledge. They also need to be supported by a continuous improvement culture. By following these three steps, mining companies can help their employees comfortably climb out of the valley.”

Change starts at the top and a positive attitude at the top is a must. Looking at AHS as more of a journey rather than a destination, it’s much easier to accept that there will be obstacles along the way, but with a clearly marked roadmap, some of those obstacles can be avoided, Gillespie said. “Employees are going to feel fear when they take on AHS,” he said. “The fear arises from doing jobs that they have traditionally done manually. They feel fear for their changing role and the unknown. Fear can really bog down the journey through the valley.”

Process is one of the most important things to combat when taking on AHS. Mining companies need fully defined processes that are going to be used with the AHS system, which requires collaboration and repetition. Gillespie suggests organizing a focus group while the fleet is still operating manually to understand what processes will need to be in place for the new system.

The focus group should review the current processes, ask and answer questions, like: Is the current process working? What needs to be done to adjust them to better suit AHS? Is this the most effective way to use the equipment? Is it this the best way to design the mine? What changes would complement AHS succession planning? Does the succession planning process suit the AHS model? How can it be improved?

These processes will need to be clearly defined when it comes to operating AHS. Once the team thinks they have answered every question and solved every problem, and gone through every scenario, Gillespie said management should make them do it again. And then do it again once the new technology is in place. “That is the time to be even more thorough about scrutinizing the processes,” he said. “Have a look at your high achievers. What are they doing differently? Can you incorporate that into the AHS processes? Have a look at your lower achievers. Is there something simple they are missing? Can the high achievers be mentors for the lower achievers?

“Miners are truly amazing people, but their ability to operate machinery in a manual environment does not easily adapt to an AHS environment,” Gillespie said. “They will need advanced skills and knowledge to unlock the potential with AHS. They’re very capable in their current roles, but a lot of their skills will need refining to become effective to operate the new technology.”

Despite the most detailed instructions, people who assemble IKEA furniture always end up with one or two screws at the end, or they discover that they have installed the first piece upside down and they need to return to step one and start over. “That’s how it will feel for employees when they take on AHS without advanced level coaching and knowledge to help them along the way,” Gillespie said. “Implementing AHS without expert know-how and support will feel super frustrating for employees and some of them will give up before even trying. The OEMs provide excellent technical support to make sure the equipment functions the way it’s expected to, but the ability to adapt from hands-on to AHS Mining is a massive change.”

In a role that typically requires hands-on work, however, translating that to AHS will feel frustrating because they excelled at a job that they have done for a very long time. “As managers, investing in training for employees is one of the most important things that can be done to ensure productivity and build a continuous improvement environment,” Gillespie said. “Engaging with experts at every step of the way to make sure the system is operating the way they want it to operate to answer their questions and ease their concerns is vital.”

Establishing a workplace culture that not only fosters growth, but strongly encourages it is critical. “A continuous improvement culture is one where employees feel comfortable trying new things so that if and when they fail, they know that you have got their back because you recognize that’s the only way to grow,” Gillespie said. “As managers, we can agree that we have heard one too many motivational speeches to empower employees with phrases like ‘the only thing to fear is fear itself,’ and ‘you aren’t growing if you aren’t failing,’ right? These sayings are motivational. Take them to heart. And if you never pull them out at any other time, do it when implementing a revolutionary change like AHS.”

“Leaders lead,” Gillespie said. “They don’t wait to see what their employees, businesses, or followers might do with change. They take charge and create monumental success. After they succeed, they keep challenging the status quo by pushing AHS operating boundaries without losing connection with key safety procedures. Being empathetic, transparent, and supportive will be the best way to level up your AHS strategy.”