Iron ore miner Fortescue Metal Group’s new integrated operations center, called the Hive, provides the technology

needed to serve its supply chain. Also,

Iron ore miner Fortescue Metal Group’s new integrated operations center, called the Hive, provides the technology

needed to serve its supply chain. Also,

according to FMG CEO Elizabeth Gaines, the center will underpin the

company’s future use of artificial intelligence and robotics and will expand to

include the generation and integrated

distribution network for its Pilbara Energy Connect solar-gas power project.

Like other basic industries, mining has

traditionally been bound by chains —

sequences of connected events, actions,

expectations or demands regarded as essential

for efficient business operations.

Localized developments that spiraled

outward into global scope during the

pandemic’s first wave in 2020 — factory

shutdowns, workforce disruptions, supplier

failures and delays, for example — dissolved

some of those chains as if they were

made of paper mâché. Prices and demand

for industrial metals suddenly plummeted.

The consensus, however, seems to be

that the mining industry, using experience

and ingenuity gained from years of dealing

with globally scattered, remote and

often diverse operations, navigated these

waters more successfully than many other

major industrial sectors. Recent management

reports to stakeholders also indicate

that the pandemic succeeded in focusing

industry attention on complex supply-

chain lessons that, surprisingly, can

be expressed in simple terms: Optimize,

localize, diversify, digitalize. Get and stay

agile. Be resilient.

Resiliency is not an inherent strength

in many modern, just-in-time supply

chains that are optimized for cost and

centered around a few geographies and

vendors, Ernst & Young Global Metals

& Mining Leader Paul Mitchell noted in

a brief article last year. The days when

miners didn’t need to understand the

complexities across their supply chains

are gone, he argued, but there are steps

that can be taken to mitigate disruption

and cultivate a deeper understanding of

supply-chain intricacies.

These include:

• Conducting an end-to-end supply chain

risk assessment to develop a calculated

risks index. The assessment should

include demand and supply risks, operational

performance, global trade implications,

and the impact on customers

and the workforce.

• Identifying supply chain gaps by developing

crisis scenarios based on how long

disruption may continue. Activating existing

crisis management policies and protocols

in each scenario can identify gaps

in the current supply chain model.

• Prioritizing critical focus areas that may

have changed in light of current circumstances

— for example, personal

protective equipment, food and provisions,

spares and equipment.

• Investing in more collaborative, agile

planning and fulfillment capabilities,

which may include, for example, sharing

inventory with other mining and

metals companies in the same country.

• Ensuring good visibility of commodity

demand — and protection if it doesn’t

eventuate. A clear view of demand helps

companies direct stock to the most

important work.

• Reviewing contracts to determine

whether a company and its suppliers,

contractors or subcontractors have force

majeure rights.

“When supply chain structures are no

longer fit for purpose, companies will need

to act fast — first, to ensure continued inbound

and outbound flows of products now

and, second, to build a more resilient supply

chain for the future,” he concluded.

Not so Simple…

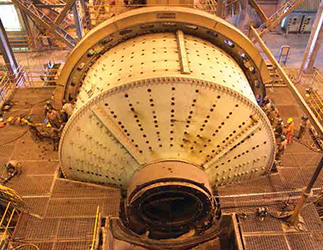

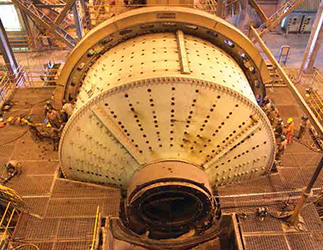

Every year, processing equipment manufacturer

FLSmidth makes 750,000 supplier

deliveries and 250,000 customer

deliveries — representing 90 deliveries

every hour of every day. Asger Lauritsen,

chief procurement officer at FLSmidth,

recently explained the company’s strategy

for maintaining a smooth flow of inbound

and outbound material even in the face of

a global pandemic.

“Seen from one perspective, it is a very

simple task — goods need to be moved

from one place to another — but in reality,

there is an almost endless amount of

details that create additional complexity.

When something like COVID-19 occurs,

things can get even more tricky,” he noted.

“We find the best local suppliers for a

specific component and, once they have

proven their reliability, we help them grow

in that region but also help them expand

into the global market. In this way, we can

support the local business community in

the areas where we work, while making

our supply chain more agile.”

The result, said Lauritsen, has been that

FLSmidth experienced very few disruptions

in the supply chain: “With minor exceptions,

all our sites have been operating at all

times 90%-100% — and on-time delivery

has been equal to the last year’s high level.

“We have redundancy built into the

system. This gives us greater flexibility and

agility and we have developed a network of

producers and suppliers on all continents

who can complement each other. We started implementing this structure before

anyone had ever heard of COVID-19, so in

that regard we have enjoyed a little bit of

‘lucky timing,’ while other companies with

a more centralized supplier setup have

faced bigger challenges.”

He went on to explain that given the

company’s high number of external suppliers,

“We are much more agile than many

competitors. We are running an asset-light

model and have not invested in expensive

production facilities because we have nurtured

a trusted network of suppliers in the

right locations with the right capabilities.

It is a solid mix of make/buy and insourcing/

outsourcing — this allows us to shift

quickly between different suppliers in different

parts of the world.

“Our ultimate goal is to look at outsourcing

everything that makes sense to

outsource. It can easily end up being a

quite high percentage. What we add to

the process then is design, commissioning

with our specially trained engineers,

who guarantee the quality, uptime and

continuity with our support.”

The final piece of the supply chain puzzle,

he explained, is digitalization, which

“provides benefits such as deeper insights

into customer requirements, developing

demand in certain regions or commodities,

and a simplified overview of the entire

supply chain, updated in real time. The

efficiencies and streamlining supplied by

digitalization and data analytics are also

helping us move toward a CO2-neutral supply

chain, which is one of our priorities.”

New Additions

Additional chains also have emerged in

response to mining’s appetite for technical

innovation and expanded awareness

of social responsibility, such as chains of

custody to ensure claims of appropriate

mineral origin, expanded chains of management

accountability, and who hasn’t

heard of blockchain, a hot-topic digital

asset management concept that few

non-techies fully understand?

Although the function of these newer

chains is the same — defining a pathway

to achieve a specific outcome or behavior

— the composition of the links that form

them is changing. Unlike familiar transactional

chains linked by customary practices,

reams of spreadsheets or stacks of

standard operating procedures, new chains

are likely to be forged from data streams,

algorithms and artificial intelligence.

Digital technology now allows producers

to model, tweak and stress-test various

value-chain scenarios for maximum

efficiency, with the goal of bringing the

enterprise’s supply chain data flow up to

speed with its product flow.

For an industrial giant such as Caterpillar,

for example, that can be a tall order;

it has thousands of ground, ocean and

air “lanes” in its supply chain structure,

moving literally billions of inventory items

ranging from a few inches in size and a

couple of ounces in weight up to pieces

weighing more than 100 tons and measuring

50 feet long or more, to dealers and

end-user customers around the globe.

Digital solutions help FLSmidth strengthen supplier relationships during the

Digital solutions help FLSmidth strengthen supplier relationships during the

most severe periods of the pandemic,

says Asger Lauritsen, the company’s

chief procurement officer, ‘Advanced digital solutions allow us to stay in

daily

contact with key stakeholders and suppliers globally.’

But recent developments have shown

that size and weight aren’t accurate indicators

of importance for items in the

supply chain. Caterpillar’s chief financial

officer, in an interview with Bloomberg in

April, warned that production could be

affected later this year by a global microchip

shortage that’s already causing problems

for automakers and consumer electronics

manufacturers — in other words,

a major company risks being pushed off

course by a shortage of computer chips,

probably the smallest active component

in any of its mining-class trucks, shovels,

drills and dozers.

Beyond Digital

Many challenges associated with the upkeep

of outbound/inbound supply chains

are of a distinctly nondigital nature, such

as climate change, politics or stakeholder

preferences. For example, global warming

can lead to water scarcity or unavailability

— a make-or-break concern for new or

expansion mine projects and a significant

supply-chain issue when extreme weather

results in disruptions to factory output

and transport availability.

The political realm poses additional

concerns: The World Bank estimates that

80% of global trade, at one point or another,

passes through countries with declining

political stability scores, and other studies

have pointed out that hundreds of product

categories have manufacturing sources

dominated by just one country. Meanwhile,

investors are paying more attention

to a company’s ethical practices, corporate

culture and commitment to social responsibility,

while producers are focusing less

on dollars-and-cents transactional details

and more on macro-level changes needed

to derisk their supply chain.

All of these issues are underscored by

the fact that miners, unlike computer chip

manufacturers or automakers, can’t just

move operations back onshore or near-shore to avoid supply chain complications.

Minerals are where you find them, and increasingly

they’re being found in harder-toreach,

undeveloped locales that may lack

supporting infrastructure, stable government

or an experienced workforce. So, mineral

producers are innovating — adopting

policies that involve supply chain initiatives

to assure customers that the commodities

they’re buying have been produced in accordance

with ESG principles, convince

local and national governments that mining

operations can have a positive social impact,

and cultivate sources of funding in an

increasingly activist investor environment.

For example, Rio Tinto recently launched

START, intended to help its aluminum customers

meet demand from consumers for

transparency on where and how the products

they purchase are made. According to

the company, START will empower end-users

to make informed choices about the

products they buy and to differentiate between

end products based on their environmental,

social and governance credentials.

Customers will receive a digital sustainability

label — similar to a nutrition label

found on food and drink packaging — using

secure blockchain technology. It will provide

key information about the site where

the aluminum was responsibly produced,

covering 10 criteria: carbon footprint, water

use, recycled content, energy sources, community

investment, safety performance,

diversity in leadership, business integrity,

regulatory compliance and transparency.

Through START, Rio Tinto will also

provide technical expertise through a

sustainability advisory service and support

for customers looking to build their

sustainability offerings, benchmark and

improve performance, support sourcing

goals and access to green financing.

A South African business unit of Anglo American lent its engineering expertise to assist medical

A South African business unit of Anglo American lent its engineering expertise to assist medical

students at a local

hospital in quickly producing COVID-19-protective headgear components with

3D printing. The company recently

announces that it’s now exploring the possibility of producing

spare parts for its mining and process equipment

using the same technology.

Multi-mineral producer Anglo American

said it has committed to reaching a

goal of having at least half of its operations

undergo third-party audits against

recognized responsible mine certification

systems in 2021, and all of its operations

audited by 2025. Among other initiatives

aimed at supply chain optimization, in

May, the company announced it has partnered

with the South African Council for

Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)

and U.S.-based technology company,

Ivaldi Group, to explore opportunities to

digitally distribute spare parts for mining

and processing equipment to be manufactured

locally using 3D printing.

The project includes an analysis of Anglo

American’s inventory of spare parts, such as

impellers for pumps, shaft sleeves, gasket

bonnet valves, and rock drill bits, exploring

the impact of adopting a digitally distributed

supply chain, and then digitizing, locally

producing and testing these parts at Anglo

American’s operations in South Africa.

Matthew Chadwick, head of socioeconomic

development and partnerships

at Anglo American, said, “The ability to

send files — not physical spare parts —

will reduce our carbon footprint, delivery

lead times and logistics costs. Importantly,

this has the clear potential to create

industrial and service jobs for host communities

and surrounding regions through

on-demand manufacturing systems to

produce spare parts locally.”

Building Out Blockchain

End-user interest and actual usage of

blockchain digital ledger technology is escalating

as mining companies develop a

better understanding of its practical value

and availability. One of the most recent participants

is Nornickel, the largest producer

of palladium and high-grade nickel and a

major supplier of platinum and copper.

In January, Nornickel said it would

join the Responsible Sourcing Blockchain

Network (RSBN), an industry collaboration

among members across the minerals

supply chain using blockchain technology

to support responsible sourcing and production

practices from mine to market.

The move to join RSBN, said Nornickel,

came after it announced a broad strategy

to use digital technologies to create

a customer-centric supply chain, which

would include metal-backed tokens on

the global Atomyze platform, a tokenization

platform that represents physical

assets in digital form.

Nornickel said that after joining the

RSBN, a series of its supply chains will

be audited annually against key responsible

sourcing requirements by RCS Global.

The audits cover each stage of the company’s

vertically integrated operations from

Russian mines to refineries in Finland and

Russia. Once audited against responsible

sourcing requirements, each supply chain

will be brought on to the RSBN and an

immutable audit data trail will be captured

on the platform, proving responsible

nickel and cobalt production, its maintenance

and its ethical provenance.

Built on IBM Blockchain technology

and the Linux Foundation’s Hyperledger

Fabric, the RSBN platform is claimed to

help improve transparency in the mineral

supply chain by providing a highly secure

record that can be shared with specified

members of the network. Additionally, RCS

Global Group assesses each participating

entity both initially and annually against

responsible sourcing requirements set by

the Organization for Economic Cooperation

and Development (OECD) and those established

by key industry bodies, including

the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI).

Now that climate change and pressure

to “decarbonize” have become constant

factors in management guidance throughout

the entire mining value chain, the

scope of these concerns, once confined

to a company’s directly controllable operations,

now extends to its sources of supply as well as its outbound product

flow. In December 2020, the World Economic

Forum’s Mining and Metals Blockchain

Initiative (MMBI) released a proof

of concept, known as the Carbon Tracing

Platform, that uses blockchain to track

embedded greenhouse gas emissions

to help producers ensure traceability of

emissions from mine to the final product.

The founding members of MMBI, Anglo

American, Antofagasta Minerals, Eurasian

Resources Group, Glencore, Klöckner

& Co., Minsur, and Tata Steel, joined

forces in October 2019 to design and

explore blockchain solutions to accelerate

responsible sourcing in the industry. By

pooling resources and costs, the mining

and metals companies aim to accelerate

future adoption of a solution for supply-

chain visibility and ESG requirements.

According to MMBI, it not only tests

the technological feasibility of a solution,

but also explores the complexities of the

supply chain dynamics and sets requirements

for future data utilization. In doing

so, the proof of concept responds to demands

from stakeholders to create “mine

to market” visibility and accountability.

The proof-of-concept work, said the organization,

lays the foundation for the next

phase of development and reinforces comprehensive

feedback sessions with stakeholders.

It also supports the MMBI vision

to enable emissions traceability throughout

complex supply chains and to create “mine

to market” visibility and accountability.

Integrate, Illuminate

Producers are also tightening up their internal

organizational structure and technology

resources to handle future supply chain

demands. In a Q4 2020 earnings call held

in late March, an executive of Polish copper

and silver producer KGHM called attention

to a supply chain project that the

company said had paid off handsomely

by integrating three processes: resource

planning, supplier procurement and inventory

management. “Now,” said Radoslaw

Stach, vice president of the management

board for production, “that integration and

digitization and automation of these processes

translated into enormous cost savings

in real-time, and we could watch the

results as we rolled out the program in the

fourth quarter of 2020.”

Another strategy gaining momentum

is improved visibility of the chain through

implementation of a “control tower” concept

— as explained in an analysis of supply-

chain agility progress in mining published

by Deloitte earlier this year: “While

many mining companies have taken steps

to mitigate risks in their supply chain,

for most, the true nature of the risks still

remains unknown,” wrote report authors

Chris Coldrick, a consulting partner based

in Australia, and Rhyno Jacobs, an operational

engagement expert with Deloitte’s

Africa Strategy and Operations business.

“The rate of response and priorities

have varied; however, there is still a need

for companies to assess and manage the

risk by illuminating the extended inbound

supply network and actively managing

it through a so-called control tower

view: a central hub with the required

technology, organization, and processes

to capture and use transportation data

to provide enhanced visibility. Balancing

the inherent risk with continued cost focus

will likely be key.

“Risk mitigation strategies should then

follow suit, including establishing alternative

supply sources — with an emphasis

on building a sustainable local supply

base — and reevaluating inventory strategies

to have greater control over access to

critical spares,” according to the authors.

As an example, Fortescue Metals Group

officially opened its Hive in mid-2020, an

expanded Integrated Operations Center

(IOC) in Perth, Australia, that provides

the technology needed to serve its supply

chain. The purpose-built facility includes

FMG’s planning, operations and mine

control teams, together with port, rail,

shipping and marketing teams. The newly

refurbished space allows more than 300

team members across Fortescue’s supply

chain to work together, 24 hours a day,

seven days a week, to deliver improved

safety, reliability, efficiency and commercial

outcomes, according to the company.

Fortescue CEO Elizabeth Gaines said

the center seamlessly links the company’s

core exploration, metallurgical, mining

and marketing expertise to deliver

value to customers, shareholders and the

broader community.

However, not all technological tools

need to be all-encompassing. There are

also opportunities for improvement using

technologies that focus on smaller fields

of play, such as site maintenance. Global

mining supply chains are dependent on

the reliability and performance of physical

assets such as mine fleets, stockyards,

warehouses, transportation modes, terminals

and ports. The industry’s financial

health is tightly tied to the maintenance

of steady outbound material flow from

the pit to the plant and ultimately to the

customer. Conversely, the inbound flow

of parts, consumable materials and other

supplies needed to support a mining operation

must be equally efficient to keep the

outbound product stream moving.

One of the pillars of efficient production

is access to a field service management

system that, at a basic level, schedules

work orders, dispatches technicians,

tracks labor hours and job status, and

archives completed jobs that, in the mining

industry, are often done by workers or

crews that may not be in constant contact

with the office and are carried out in rugged

outdoor environments.

E&MJ asked Travis Parigi, CEO and

founder of LiquidFrameworks, a software

developer that markets the FieldFX suite

of field service management (FSM) modules,

to point out some indications that

a mining company could benefit from an

FSM system.

“A field service management solution

is needed once a company finds that its

paper processes have grown to a point

whereby labor and processing time have

become barriers to scale and increased

efficiency,” Parigi said. “Losing field documentation

or delaying the collection of

field documentation that negatively impacts

the company’s financial health is

another indicator. A lack of visibility into

centralized, accurate and timely data for

the purpose of business intelligence reporting,

which makes for more difficult

decision-making, is also another sign.”

He also said that the latest generation

of FSM products can accommodate the

diverse nature of mining: “FSM solutions

can accommodate a wide variety of configuration options found at mining companies,

especially if sites are dispersed

across multiple countries. Options for

internationalization and globalization include

a series of features to support multiple

languages, multiple currencies and

workflow configurations that can vary

based on geography and division.

“Modern, cloud-based FSM solutions

suited for enterprise mining operations

can be maintained and undergo software

updates with resources and effort much

lower compared to legacy on-premises

solutions,” he added.

As featured in Womp 2021 Vol 09 - www.womp-int.com