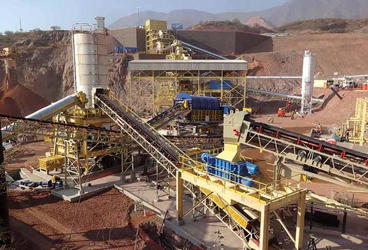

Kappes, Cassiday & Associates specializes in heap leach and cyanidation plants for small to midsized gold and silver operations.

(Photo: KCA)

Delivering Mining’s Most Challenging Projects

Designing and constructing a greenfield plant is one thing,

but a brownfield expansion is hands down more difficult

By Carly Leonida, European Editor

Some of these are plant expansions to increase capacity or upgrade aging flowsheets, others aim to boost throughput by accessing new areas of existing or adjacent orebodies. Whatever the objective, planning, designing and executing these already complex projects has been made an order of magnitude trickier recently thanks to the likes of COVID-19 and social distancing. In a bid to better understand the nuances of these projects, E&MJ turned to four companies that are navigating current waters with success. First up was Canada-headquartered global engineering and consulting firm, SNC-Lavalin.

“There’s a lot of expansion activity right now, especially in gold and base metals,” César Inostroza, senior vice president, mining and metallurgy, said. “Most of our activity is in brownfield projects and concentrator upgrades. At the beginning of the year, there were some greenfield projects getting ready to launch, but then COVID-19 hit. That created a lot of uncertainty in commodity pricing and many mining companies have adopted a ‘wait and see’ attitude for the next six to nine months. “In the meantime, existing plants are going gang busters trying to squeeze out more production. The gold space is very busy for us, as are nickel and cobalt, and the PGM market is also starting to move again.”

Fellow multi-sector, multi-commodity behemoth, Wood (which gained a foothold in the mining market in 2017 through the purchase of AMEC Foster Wheeler), reported similar. “The primary drivers for project development are commodity price and quality,” Vice President for Global BD and Consulting Services Mike Woloschuk said. “Copper, zinc and nickel pricing have surpassed pre-COVID levels. Iron-ore prices are back to levels seen during the 2009- 2013 super-price cycle. Gold has hit peak price and silver has outpaced them all. Projects that were marginal at lower prices are now viable and the increase in project activity is occurring in all regions.”

Kappes, Cassiday & Associates (KCA), based out of Reno, Nevada, primarily serves small to midsized precious metal mining operations. Caleb Cook, project engineer, explained that KCA has seen a lot of interest recently from clients, both existing and prospective, with regard to expanding or upgrading their facilities. “We usually see a trend whenever the gold price jumps by 20% or more, that exploration projects start moving into the metallurgical test work or PEA phase,” he said. “A lot of greenfield projects have slowed down in terms of construction activities, but junior exploration companies have become very active with higher metals processing. COVID has not seemed to hurt the ability of juniors to raise small amounts of money, but the big deals are still moving slowly.

“In particular, we’ve noticed an emphasis on U.S. projects, whereas traditionally a significant portion of KCA’s work is outside of the U.S., especially in Mexico. We believe a lot of this is due to travel uncertainties and economic effects related to COVID-19. “With travel restrictions, there’s been a lot of work that we haven’t been able to do in our usual way. For brownfield projects, that’s meant relying a lot more on local groups to do the fieldwork. We’ve also seen some work postponed for the near term until things settle down. There’s definitely been a big impact. And as a result of that, a lot more of our work has been on U.S. projects.”

Working Through COVID

E&MJ asked Inostroza how COVID-19 has

affected SNC-Lavalin’s brownfield projects.

“About 80% of our current work in

North America is in engineering, so it’s

mainly desktop based,” Inostroza said “We migrated our North American offices

in Montreal and Toronto from office based

to virtual in the space of a week, and

we’ve not seen much of a hiccup in that

process, because we were already accustomed

to working with collaborative tools.

“That could change when some of these projects move into the construction management phase next year. At that point, we hope that the COVID crisis will be controlled to the extent that we can manage the mobilization of people on site. “In Brazil, we have three projects in execution, so the impact of COVID was felt more by those sites. There was a period where we had to suspend operations while the situation was developing and now, we have resumed activities. Our biggest client there is Vale and they haven’t slowed down for one minute. We have around 1,200 people in Brazil and they’re working at capacity.

“In Peru it’s different, because the mining industry there went through a total shutdown for quite a long period. We had about 150 people in a construction management role in Antamina in northern Peru and the mine there was completely stopped. We’re now starting to send people back as activities resume. COVID has had an impact on our ability to deliver services on remote sites in locations like Peru. “Some clients are now looking to the future, and what to do post-COVID at those remote sites. We’re getting a lot of interest in remote operations, remote supervision, remote sensing… so that clients can operate these facilities with minimum numbers of staff should this happen again.”

“Then there are interfaces to tie into the existing operations, be it physical interfaces or systems interfaces, people… that complicates matters tremendously. “The only solution we know for that is planning, and then extensively developing the interface management plans to identify all the steps where we need to connect the two from a people, safety and design perspective; identify as many touch points as possible so we can manage them one by one. That’s the only way you can deliver projects of this nature with the least amount of impact to the existing facilities.” Given all these ins and outs, SNCLavalin is a fervent proponent of the stage-gate process.

“We strongly believe that’s the best way of approaching any project, whether it’s an expansion or a greenfield,” Inostroza said. “You get to demonstrate the business case at every stage to justify whether it is worthwhile proceeding with the next step or not.” First, the company approaches the project on a conceptual study level to minimize the amount of investment upfront and justify the cost benefit. Next comes the technical evaluation: identifying the ore’s properties, test work to justify the flowsheet, flowsheet design, finding the layout and footprint of the plant, coming up with the capital and operating costs and the economic analysis to build a more robust business case. If the numbers add up, then the next phase involves defining those areas to a greater degree of accuracy.

“That’s normally how we work,” Inostroza explained. “Certain clients want to bypass the whole process or skip steps, but we always tell them that if they want to minimize their risk exposure then stick to the program and do your homework first; it’ll pay off in the end.” For KCA, the first step in planning a mine or plant expansion starts with an assessment of the orebody and the ore grade that can be maintained and at what production rate. This may require adding, expanding or modifying an existing circuit to improve recoveries or expanding the system to increase production rates. Often, the expansion involves a move to a different type or grade of ore, so part of the design process is getting the operation to discuss what changes might be needed. Small and medium-sized companies may only have one cashflow generating project, so expansion becomes a very sensitive topic.

“In most cases, the client has already performed some preliminary test work and high-level cost analysis for the planned process or expansion,” Cook said. “Once enough information is available and the expansion is defined (general flowsheet, throughput, target product size, recovery, etc.) we can begin evaluating the client’s existing plant, and how we can achieve the plan without disrupting production.” Wood’s approach to expansions focuses on maximizing the project’s net present value (NPV). “The drivers to maximizing project NPV must consider all aspects of the operation including the mine, on-site and off-site infrastructure, process plant, and waste storage and treatment facilities,” explained Woloschuk. “We have in-house technical and project delivery expertise in all these areas. An integrated team enables us to effectively collaborate to deliver the best project outcome.”

Wood’s Santiago office has developed a computer simulation that identifies and relieves bottlenecks in processing plants using the mine plan and incorporating geometallurgical parameters into the resource model. The outcome is a sliding scale of expansion cost versus increased output, allowing the owner to make the best decision based on maximizing NPV.

KCA’s Cook added, “Most clients we work with prefer the EPCM model, especially with expansions, because they want to be part of the equipment selection and decision making for the project. EPCM contracts are also generally less expensive compared to EPC contracts, which typically include high contingencies by the contractor to cover their cost liabilities.” EPC contracts do tend to carry more risk for the contractor, and this is something that SNC-Lavalin has taken a firm stance on. Inostroza explained, “The typical EPC lump sum turnkey model assigns a significant portion of the risk to the contractor as opposed to sharing it with the client. It got to the point where that model was essentially flawed, because contractors were expected to assume too much risk, even in areas they couldn’t control. So, we have clearly stated that we will no longer do EPC lump sum contracts.

“Our preference is to work collaboratively with clients in an EPCM mode, which is a reimbursable type of contract or with a fixed price. We will work with clients on a consultancy basis, we will help them do construction management, and we will do project management consultancy (PMC) where necessary. We remain a project delivery organization, we’re just not doing the flawed EPC lump sum turnkey contract model. “The selection ultimately depends on the client’s appetite for risk and the level of involvement they want to have in the decision making of the project. Some clients have a limited team running a job, so they rely on this sort of support to provide the balance of the engineering and project management. Others, especially the majors, have a really strong project delivery capability, so they are more likely to engage a single entity to deliver the project with them in a strongly collaborative way.”

Specialist Management

Services

PMC is becoming a model of choice in

some jurisdictions as miners look to

deliver more scope under EPC/design

and construct arrangements. With most

of the engineering undertaken by the

contractor in this instance, the PMC

approach can be used to provide the

technical oversight, commercial management

and project controls required to

deliver the project outcomes.

Turner & Townsend, headquartered in

the U.K. and with 111 offices worldwide,

has supported major mining houses, as well

as several mid-tier and junior miners with

project management services. The company

offers cost and commercial management,

contracts and procurement and project

controls throughout the full lifecycle.

Peter Coombs, director for mining and metals, said, “Our project delivery framework supports mine owners to manage the supply chain to deliver projects within the cost, schedule and risk targets set out in the business case. The framework sets out a best practice operating model, which integrates processes and procedures with technology, enabling collaboration between engineers, consultants, contractors and technology partners. “Traditional contracting models continue to be assessed against risk and performance targets. While EPCM consultants and contractors are at the basis of the design and build of mines, where they sit within the project delivery model is changing, with options around disaggregation of EPCM to separate parties and the use of PMC or an independent integrator under consideration.

“Hybrid models can provide an alternative to the traditional delivery model but must clearly define processes, roles and responsibilities as well as interface management. Irrespective of the contracting model, we believe that having commercial management and controls provided by a party independent from the engineer can lead to improved visibility of engineering performance, enhanced management of risk, procurement, contracts and claims avoidance, plus improved transparency of project processes and governance.” Overruns and delays are common in both greenfield and brownfield projects. Project management independent to engineering can provide additional transparency on the technical and commercial performance of a project that is not always achieved in traditional EPCM delivery models. This includes early warning of increased risk or reduced performance and progress.

“Providing clients with visibility supports informed decision making and capacity to intervene,” Coombs explained. “An independent project management approach works through collaborating with the client, engineering and the project supply-chain functions, but in maintaining independence, a framework of transparent governance and progressive assurance is established. This ultimately provides a single source of truth for quality, cost, schedule and risk status.”

Turner & Townsend is currently working on several gold and iron-ore projects and plant expansions. “With reduced greenfield spend, expansion projects are dominating the mining landscape,” Coombs said. “At the same time, the drive to net zero is requiring every industry to embrace energy efficient operations and support the growth of technologies that remove emissions out of the atmosphere. As part of this agenda, we are also supporting a number of clients who are looking at both new build renewables projects, as well as adoption of new technology configurations into existing assets. “The challenge of these programs is they consist of interconnected projects, including plant construction, technology integration, storage, and grid infrastructure, all delivered in an operating environment. We are working with clients to reduce uncertainty on project feasibility, scope, cost, schedule, risk, execution strategy, constructability, and where necessary closure and decommissioning of some aspects of the existing facility. “We are also seeing a focus on optimization programs and debottlenecking, but with minimum maintenance to preserve cash and maximize output based on the current volatilities of global economies.”

The Benefit of Technology

Digitalizing and technology-enabled delivery

are now key to exceptional execution

and meeting client expectations for

innovation and cost savings. Technology-

enabled delivery picks up everything

from making safety management systems

available in an app, to digital twins for

construction projects and artificial intelligence

in engineering design.

Woloschuk explained: “One of our flagship

projects in South America involves integrating

information across lump-sum design

and construction contracts. Wood has

been able to remove duplicate tags, check

data and tag quality, and regularly update

a master model for all stakeholders. Construction

progress has been recorded with

drone photography, allowing daily progress

to be verified. This reduced capital cost

and kept the project on schedule.”

SNC-Lavalin has also been harnessing digital technology to drive value for clients. “We’ve been using virtual and augmented reality around design functions for a while now,” Inostroza said. “We can develop intelligent models and layouts… this additional layer allows us to do virtual walkthroughs and design and maintenance reviews with clients. It provides them with a lot more visibility. “We’re also doing a lot of laser scanning in brownfield projects, where we scan the whole facility to create a cloud of points. That gives us a 3D model of the installed equipment that can be imported into design tools, so that when we’re putting the new equipment in, we know exactly where it will and won’t work.

“We use drafting and rendering technology on most of our projects,” Cook said. “We model the recovery plant and the process equipment in 3D and its overlaid on the site topography so that we can do a virtual walkthrough of a rendered plant. We can see where the pipe connections and supports are, where valves are placed, and we can make sure that it’s going to be operator friendly. We can make any modifi- cations or changes to the design before we get out into the field. It’s beneficial to us and our clients, because there are opportunities to make things as ergonomic and operator friendly as possible. That’s something that we as a company really prioritize and strive for: making sure that anything we build is going to be something that operators are going to enjoy operating.

Turner & Townsend has also embraced digital workflows and developed common data environments to drive efficiencies in the delivery of projects and programs. “We have a suite of technology solutions and Digital Engineering (DE) services that have realized significant time and cost savings for clients, as well as simultaneously laying the foundations for the digital twin,” Coombs said. “Key to success is articulating Employers Information Requirements (EIR), the Organizational Information Requirements (OIR) and the Asset Information Requirements (AIR) prior to the award of engineering partners. Where this is done, benefits can be seen in reduced turnaround times for project deliverables and increased project control.”

Making Use of Modularization

The use of modules or “modularization”

is becoming ever more common as more

advanced design tools are used and as

site information is integrated from 3D

scanning. However, the selection of modularization,

preassembly or stick-built execution

models is project-specific.

Modularization can be attractive, as it

minimizes on-site labor and thus is often

less expensive, and it maximizes safety in

fabrication, logistics and construction. Cost

advantages are also gained by moving work

to where conditions are more favorable in

terms of congestion, altitude or weather.

“Modularization and ‘plug-and-play’ type components as a general rule are to simplify and speed up construction at site,” Cook said. “They are applicable to both expansions and greenfield projects but are usually more important at greenfield sites than at established mines which have the infrastructure to support on-site construction activities. “KCA builds a lot of modular plants for greenfield sites, and some ‘cookie cutter’ modules for insertion of equipment systems into existing production plants. For expansions, the focus is frequently on limiting interruptions to current production rather than condensing the construction schedule.”

Inostroza reported similar: “Any project that we get involved in, we always look at the opportunity to do modularization, whether its small-scale preassembling of certain equipment to full sized modules. In the brownfield space, modularization is generally used to optimize cost, schedule and quality. Construction is usually better quality in the shop than in the field and much safer. Also, in remote locations there can be a lack of resources for construction so the more work you can do in the shop the better. “We’re doing complete process modules and prefabricated buildings for a lot of brownfield sites, and modularized electrical substations. Nowadays, electrical e-rooms are almost always modularized. They are just shipped to site in a container and hooked up. We’re also doing modular pipe racks, which are preassembled in chunks and bolted together on site.

“With modularization the level of engineering has to be extremely well advanced. You don’t want to be in a situation where something has been designed and assembled then, once it’s on site, you find it doesn’t fit right. If that’s the case, then you lose all the benefit of preassembling the components.” Standardization is another technique that can be used to speed the delivery of certain project components and drive down costs. However, every mining operation is unique starting with the orebody, and it can be hard to fit standardized modules or pieces of equipment into custom- built plants.

“Repeat clients will often say ‘do it like the last time,’” Inostroza said. “In theory, you could shorten the cycle time for engineering and procurement because, for example, you’ve got the designs for a conveyor or crusher already done and you can hit the ground running. But, inevitably, clients change their minds and that kills the benefi t of using this ‘cookie cutter’ approach. In some circumstances, clients stick to the initial thought process, but it’s rare.”

Looking Ahead

The next six to nine months will be very interesting,

and not just in mining. Although

commodity prices are currently high, they

are a function of the overall economic climate

and how that plays out will dictate

how aggressively mining companies pursue

the development of both greenfield

and brownfield projects for years to come.

While there are a lot of studies going

on, particularly in gold, it’s hard to say

how many will come to fruition. Miners

are, quite rightly, guarding their capital

expenditure closely. One thing is certain,

if they do press the go button, service providers

will be ready and waiting to assist.