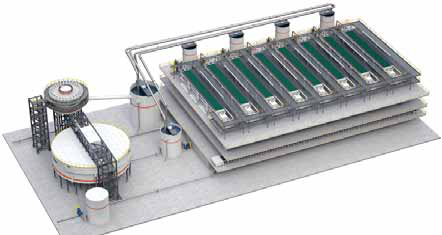

FLSmidth’s Colossal filter demo plant at Escondida in Chile.

How to Make Filtered Tailings Feasible

The technology and drivers required for dry-stack tailings are all there, so why are mines

still wary of high-performance filters, and how can we overcome the current inertia?

By Carly Leonida, European Editor

Dewatering technologies have existed for years in the form of thickeners, cyclones, centrifuges, vacuum filters, belt presses etc., and these have been widely applied at high-grade, lower throughput operations and at mines in water stressed areas. However, until relatively recently, aside from the cost of water, there has been little incentive for high-throughput, lower-grade operations such as copper or iron-ore to dewater their tailings. So, what has changed? Firstly, filtration technology. The past 18-24 months has seen the commercial availability of next-generation pressure filters that can handle extremely high throughputs and achieve very low residual moisture content in filter cakes (as low as 5%) safely and economically. And, this has been a game changer.

The industry has been talking about the potential benefits of dry stacking tailings for years. However, applications have been few and far between, mainly due to limitations in the performance of technologies and the associated capital cost. Now that filters that can handle 30,000 metric tons per day (mt/d) and more have been proven, we should, technically, see the first full-scale implementations within the next 1-3 years. Secondly, up until 18 months ago, in the majority of cases — bar water stressed operations like those in northern Chile, and in countries where dewatering is mandated i.e., Brazil — the business case for dewatering tailings at most high throughput operations just wasn’t strong enough. The past 10 years have seen a string of high-profile tailings dam failures including Mount Polley, Samarco and, most recently, at Brumadinho in January 2019. The last event in particular prompted stakeholders at all levels to take greater notice of mining practices, good and bad.

If designed or managed poorly, wet tailings storage facilities (TSFs) can pose a significant risk to human life, to the environment and to businesses and, as such, investors and governments are now leaning heavily on miners to consider more sustainable storage options for tailings. The benefits of dewatering tailings to whatever degree are clear. However, despite the necessary technology being available and, despite almost unilateral agreement from equipment suppliers, engineering firms and mining companies that dry stacking is the most promising and widely applicable method of tailings storage going forward, the industry is at something of a stalemate.

Most of this inertia can be attributed to executive and investor’s suppressed appetite for risk. There are a huge number of factors that can influence the operational and economic success of high-performance dewatering technologies. It takes time to properly evaluate and understand these, and this, coupled with a wariness of being the first to buy into a “new” technology, means the industry has yet to see a full-scale dewatering/dry stacking solution at a high-throughput operation. It is only a matter of time, but until this hurdle is overcome, the industry cannot move forward with creating a truly sustainable sector, one that can stand up to stakeholder scrutiny and reap the benefits of the green economy.

Understanding the Risk/

Payback Balance

To get a handle on where the industry is

at technology wise, and how mines can

navigate the economic/operational/logistical

maze in front of them, E&MJ turned to

two of the biggest providers of mineral processing

solutions: FLSmidth and Metso.

Todd Wisdom, director of tailings at

FLSmidth, began by explaining the evaluation

process.

“First, we try and answer a bunch of

technical and commercial questions with

the client, ranging from what’s the cost of

water at their site, because that’s going to

determine how much money they spend on

dewatering, what’s the cost of electricity

and manpower… those kinds of things.

“We look at the operational costs, in

terms of spare parts, maintenance, and

consumables. And we need to understand

other constraints around the mine, aside

from the commercial ones, like what altitude

is the site at? What’s the particle

size distribution and mineralogy of the

tailings material, which we’ll confirm

based upon the samples they send us.

“We do a desktop study to understand those constraints, and then we need to know what their TSF looks like. Is it an existing mine? If so, what was the original mine life plan? Are they getting toward the end of it? If it’s an existing mine, we’ll evaluate a sample of tailings and discuss how many years of life they’re looking to get. “A big filtered tailings solution probably needs around 10 years to be competitive and pay back the investment in the conveyors and filtration equipment. And for large concentrators that are looking at big pressure filters, like in Chile, the cost of water needs to be more than $3 a cubic meter (m3) for it to start making economic sense or they need to be very near the end of life on their current TSF. So, we can use some high-level rules of thumb to say whether we think particular technologies are applicable or not.”

Wisdom said one of the biggest misconceptions that accompanies highperformance dewatering equipment at present, is that mines need to implement an “all or nothing” approach. However, this is definitely not the case. A partial solution where mines dewater 20% or 30% of the tailings stream offers a good way to get familiar with the technology and can help minimize associated risks. “Even engineers and OEMs can fall into that trap,” he said. “If a mine has only a couple of years of life left and you can put in a process that’s going to add another five years of life to the current TSF. And you’re only going to dewater, say, 20% or 30% of the tailings, that does a lot for the mine. That allows them more time to find a longer-term solution if they think the mine life will be extended.

“It allows them to de-risk a higher performance dewatering tailing solution. One of the big issues, especially with large mines that are looking at filtered tailings, is they view it as a risk, because there’s nothing bigger than 30,000-mt/d filtered tailings operating right now — Karara in Western Australia is the largest installation. “A 100,000-mt/d mine might look it and say ‘Ok, it’s possible, the technology is there, but we’re going to give it a really high-risk factor’ and the project never makes it across the line. If they dewater just a portion of the tailings stream, then they’re not betting the whole farm on what is, at this scale, a new technology. And it allows them to de-risk the project and get something off the ground that is beneficial for them.”

“That’s pretty easy to do on the dewatering, filtration and pumping side because you, typically, have multiple pieces of kit,” Wisdom explained. “But on the conveying side, it can be more problematic. Typically, there’s only one overland conveyor, and the TSF can be anywhere from 1 km to 20 km away from the mine. “Whereas, if you’re implementing a partial dewatering solution and there’s an issue with the conveyor, say it’s down for a few days, then instead of having a completely redundant system, you can just use the original TSF. But that also requires the mine to make the decision early enough that they’ve got some capacity left.”

Finding First Partners

Where is FLSmidth at with its filtration

technology?

“The Colossal filter was designed

to handle 10,000 mt/d, and we did a

demonstration plant with Escondida in

Chile that looked at that,” Wisdom said.

“They eventually decided, I think it was

partly due to the high-risk factor, to put in

another desalination plant.

“Then we had the EcoTails Project

that we worked on with Goldcorp. That

developed a whole new filter that was able

to handle 30,000 mt/d.”

That filter, which is yet to receive a catchy name, has been dubbed the “5 x 3.” FLSmidth held an event in Nevada last year to showcase the technology which is now commercially available. However, there aren’t any full-size units in operation yet. The test filter, that was demoed at the event is a demonstration model — it only has two chambers — and was designed to test samples of tailings to help companies build a business case before purchasing the technology at full scale. “The filter itself is engineered. It could be sold if there was a client for it,” Wisdom said. “Goldcorp and FLSmidth were looking at creating a consortium to build that first demonstration plant at Peñasquito in Mexico and prove the 5 x 3 filter and associated technology. “We’re still looking for partners. It really depends on how fast different miners come forward.”

It all comes back to the old adage that miners prefer to be first to be second (or third) when it comes to selecting new technologies. And, to a degree, that’s understandable. Most mining projects carry a fair amount of risk at the front end, so to create additional risk at the backend by throwing a new technology into the mix isn’t an option for many companies… Unless of course the cost of water is so high that there will be a huge ROI or if there’s regulatory pressure.

Wisdom thought for a moment, “I would say, especially with engineers, it’s the risk factor that concerns them. They want to see more than one example of a technology installed and operating for that particular type of tailings,” he said. “There are two things we have to prove: the mechanical reliability and the process performance. The mechanical reliability can be proven at any site. The process performance, we need to prove that and scale it up based upon smaller tests. I think all of the vendors have pretty much shown that they can scale up the equipment.

Supply and Demand

“I would say every mine that I’ve been

involved with, both new and existing, in

the last few years, is evaluating filtered

tailings,” Wisdom said. “Because there

aren’t a lot of big new mines being built,

probably, the biggest market is mines that

are extending their operational life and are

looking to increase the life of their TSF.

“Gold mines tend to be smaller, in the

10-15,000 mt/d range. And, I would say

that for those smaller mines, filter technology

is very well accepted. They’re not

only evaluating it but very seriously considering

it for every project.

“There’s a couple of drivers there

technically and around profit margins.

With big open-pit mines, they’re usually

big and open pit because they’re low

grade. And low-grade mines don’t usually

have a lot of profit margin between what

it costs them to produce a ton of metal,

and what they make on that ton of metal.

There’s very little margin for variation in

equipment before it impacts on the ROI.

“Smaller high-grade mines usually have more bandwidth to play with. And, if they’re underground, they’re probably also looking at solutions like backfill. Once you start to dewater material to put it back underground, you’ve got most of the infrastructure there to dewater all of the tailings and surface-dispose the rest of it.” Wisdom’s biggest piece of advice for companies that are evaluating dewatering is not to see it as an all or nothing solution. “Especially when looking at existing mines, don’t do an all or nothing solution, because I think the optimum, in terms of payback and lowest risk, is to partially dewater the tailings stream,” he said.

“Make sure you look at all of the technologies. Don’t get pigeonholed into ‘I think this is what’s going to work’ because that’s the only equipment the vendor offers, or because you have a preconceived notion. Do a high-level conceptual study that looks at all of the options and then maybe get a more detailed study on two or three. That might potentially come out with a better solution for the mine.”

Solutions as Well as

Technology

Metso also has a high-performance

pressure filter that is ready and waiting

for full-scale deployment. The VPX was

launched in June 2019. There are currently

four models in the product range,

but the use of modules and an electromechanical

drive (rather than a hydraulic

drive system) means that each filter can

be shortened or lengthened depending on

how difficult the material is to dewater

and the necessary throughput. The pressure

can also be adjusted to maximize energy

efficiency in relation to the desired

end moisture content.

According to research by Metso, only 5% of the tailings generated globally in 2018 were dewatered to create thickened tailings or paste, and less than 1% were filtered for dry stacking. However, the company estimates that by 2025 the share of generated tailings that are dewatered will increase to 13%. Metso is so sure of the market that, in addition to launching a new product last year, it also created a business unit called Metso Tailings Management Solutions that is, as the name suggests, dedicated to advising mining clients on and creating solutions based around tailings management.

Like FLSmidth, Metso quickly recognized the need for a test unit to help clients prove the technology and build their business case before committing to a full installation. The VPX10 is a mobile pilot plant that features all the sensors and control systems of the larger VPX models, but its miniature size allows it to be transported in a shipping container and installed at, or close to, a customer’s site, complete with thickeners and hydrocyclones. The unit has proven so popular that it has a waiting list and, to help meet demand for numbers, Metso just installed a full-size pilot plant at its own facility in Sorocaba, Brazil.

“This machine is ready for tests on an industrial scale,” Gouveia explained. “It’s not a lab unit. We have completed tests for four customers in Brazil already and we have customers in Chile, Peru, Australia and India that will start sending samples to us very soon. However, that has been delayed a little due to the coronavirus. “With the tests we are going to perform with the VPX10 in our facility in Sorocaba, we expect to have results for processing different tailings, like iron, copper and gold. That was why we decided to install the plant at our own facility, because it opens up the opportunity for us to test different material from different customers. It would be great to also install this pilot plant for one specific customer. However, we will be limited to that particular application.

“Having it inside Metso, we can easily transport 1,000 liters of pulp or slurry to our own facility and process it there. It’s also a good opportunity for customers to see the filter in operation, to have the maintenance people see the electromechanical drive working, and how reliable this solution can be. “We should have two more pilot units soon: one more in the pacific rim, to serve Chile and Peru, and another in Australia, to serve that part of the world.”

Gouveia explained that the majority of inquiries have come from existing mines that are looking to expand or mines where TSFs are approaching their end of life. “At this moment, what we are hearing most from customers and EPCs is concern on fresh tailings generation,” he said. “There are a lot of TSFs today that are very close to maximum capacity without the option to be increased. Dry tailings are the best solution for those applications. “Of course, it is of interest to new operations too with environmental licensing becoming trickier. But unfortunately, as an industry, we are not seeing many new projects coming through. For the few new large projects that are coming, dry tailings are definitely being considered.”

Water Scarcity Pushes

Innovation

Again, the main concern that Metso is

seeing regards the level of investment

required for dewatering and dry stacking

solutions, and their effectiveness.

“We all know that the mining industry

is very conservative. It’s difficult to make

mining companies move on a new technology,”

Gouveia echoed Wisdom’s words.

“All the studies that we have done so

far show that dry tailings are the future.

Not only because the risk related to tailing

dams is eliminated, but also, we are

seeing that with the new technology and

all the cost involved with tailings management,

the CAPEX and OPEX actually work

out to be more efficient with dry tailings.

“New technologies like the VPX, they put a new perspective on the financial side of tailings management, because they can handle a much higher capacity. That was the problem in the past. We had good equipment to reprocess or dewater tailings. However, the volume of water that could be recovered was low, so the cost became too high. A large number of filters were needed to cope with the volume of material but now, with these new technologies, it is very different.” Gouveia also emphasized the issue of water scarcity; something that is only going to get worse in the coming years, particularly in areas like northern Chile where many of the big copper mines are located. The region is currently experiencing its worst drought for more than 100 years, and the lack of water is leading many mines to reduce their operations or even consider halting them.

To help mines assess and evaluate potential solutions, Metso is currently developing a digital tool or “configurator.” This value calculator allows mines to enter their main priorities i.e., energy efficiency, water consumption, footprint etc., as well as information on the volume and types of tailings they’re producing and do a preliminary assessment on different circuit configurations. The tool can advise how many filters will be needed and even size the units. “It’s going to be a great tool to help customers in the decision process for going to dry tailings. We are going to launch it in phases starting in June. It’s really impressive what can be obtained with this configurator, and how quick we can respond to customer expectations,” Gouveia added. “The first phase will focus on dewatering and, later, we’ll expand the tool to reprocessing and even other stages of mineral processing. We’ll also connect it to our VPS configurator, which is already known in the market, for circuit simulations.”

What About Reprocessing?

Fresh tailings may be miner’s main concern

at present, but what about the hundreds

of billions of tons of tailings currently

sitting in dams, both operational

and closed, around the globe?

Select mines have been reprocessing

high-grade tailings for some time, but

now that the technology is available to do

so at a large scale and, now that mining

companies can no longer afford to turn a

blind eye to TSFs after closure, interest

must be growing.

“I wouldn’t say there’s a lot of interest, but there’s definitely some, especially from older mines that maybe didn’t have as good separation technology or techniques early on in their mine life,” Wisdom said. “There are definitely TSFs that they could look to reprocess and recover copper or gold or whatever is potentially still in those tailings.” Gouveia agreed, “There is great potential for reprocessing, mainly at older mines where the tailings were produced using older technologies, say, 30-50 years ago. Some of those tailings are really rich. Our studies indicate that metals obtained from reprocessed tailings can be up to three times cheaper than virgin ore. Some iron-ore mines have 50%-55% metals content in their tailings, which is amazing really. And there are copper operations with 0.5% of copper in their tailings which is higher than what’s in the ground. It’s just a question of dredging the material and floating the metal or using magnetic separation.”