San Juan Caldera—The area includes the drainage basins of three main tributaries: Mineral

Creek, Cement Creek and the Animas River. Elevations range from 9,305 feet in Silverton,

Colorado, to more than 13,800 feet in the surrounding mountains.

Remediation Helps Rescue a River

Long-term reclamation projects lower the historically high-metal loading

in the Animas River

By Steven Lange

Sunnyside Gold Corp. (SGC) was formed and acquired the Sunnyside mine in 1985 and mined it from 1986 until 1991 under modern environmental regulations and using modern mining techniques. Since 1985, SGC has engaged in more than 30 years of reclamation and remediation in the Silverton Caldera. This article analyzes the geologic setting and historic mining that have caused the metals loading in the Animas River as well as the effect of SGC’s mining and extensive reclamation activities. It is also details how the remediation actions that SGC has taken have substantially reduced acid rock drainage and metals loading in the Animas River.

The Sunnyside mine is located approximately 8 miles north of Silverton, in the Eureka mining district. The Eureka mining district is in the northern portion of the Silverton Caldera, which is part of the San Juan Volcanic complex, which was active during the mid-Tertiary (25 to 35 million years ago). The area is naturally mineralized, has been for millions of years, and forms part of the Upper Animas River basin.

A large volume of literature has been generated on the geology and mineralization of the Silverton area, but the major structural feature in the area is the northeast-trending Eureka Grabben. An intricate system of radial fractures and faults, including the Ross Basin and Bonita faults, formed around the San Juan Caldera and provided the pathway for mineralizing solutions and locations for deposition on the vein deposits.

Widespread propylitic alteration in the area has affected many cubic miles of volcanic rocks throughout the Eureka district and beyond. Pyrite is ubiquitous in the propylitized rocks, which forms 0.1 to 2 weight percent of the rock mass. It is estimated that hundreds of million tons of pyrite is present in the rocks in the vicinity.

Natural weathering of altered and mineralized rock can be an important source of metals and acidity to surface and ground water. Weathering of the altered rock in the Upper Animas basin over the last million years provided a natural source of metals and acidity to the basin waters long before mining began. Historically, parts of Cement and Mineral Creeks were always acidic, contained high-metals loads, and likely did not support any aquatic life other than species of algae that can tolerate a pH less than 4.

Franklin Rhonda, a topographer with the 1874 Hayden Survey who worked in the Silverton area, described the water in both Cement and Mineral Creeks as iron sulfate waters that were undrinkable. Pre-mining geochemical conditions in Cement Creek were not very different than they are today. A viable macroinvertebrate community probably did not exist in either Mineral Creek upstream from the confluence with South Fork Mineral Creek or in Cement Creek prior to mining.

Before the first miner arrived, there was massive natural metals loading in the Animas River, which limited aquatic life, including trout populations downstream from Silverton.

Historic Mining

As early as the 1700s, Spanish explorers

discovered placer gold in Arrastra

Creek, a tributary of the Upper Animas

River. Serious mineral exploration began

in the early 1870s, following discovery

of placer gold by the U.S. Army’s Baker

reconnaissance team. In the 1870s, the

Upper Animas watershed became a prime

location of mining activity for gold, silver,

lead and copper. The area contains more

than 1,500 mines.1 In addition, the area

was home to more than 50 separate mill

sites, eight distinct smelters and 35 different

aerial trams.

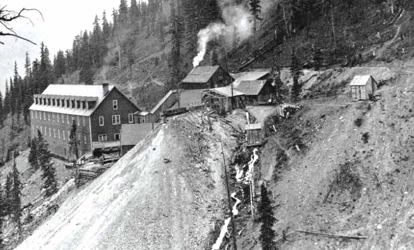

Mining and milling processes in the Animas River watershed were typical of those practiced throughout the West in the 19th and 20th centuries. Beginning in 1872, vein deposits were mined underground by small crews who selectively mined high-grade ore. Ore was hand-sorted and sent to smelters by mule pack train and later by wagon. Waste rock was discarded in open mine stopes or on mine-waste dumps outside the portal where the hand sorting was done.

As more efficient methods of mining and milling were developed and rail transport became available, increasingly larger amounts of lower grade ore were mined and processed and additional metals recovered. For example, before 1917, the available mineral processing methods could not recover zinc so it was discarded with the other tailings. After 1917, zinc was recovered from the ore. Waste rock was disposed of in waste dumps outside the mine portal, and mill wastes were deposited into the nearest stream course. An estimated 8.6 million tons of mill waste, about 47.5% of the total ore produced, was discharged directly into surface streams between 1872 and 1935.

Even when tailings were impounded rather than expelled directly to area streams, significant discharges took place. In 1947, the sand wall on the Mayflower tailings impoundment No. 1 collapsed and a large quantity of waste and tailings spilled into Boulder Creek and then the Animas River.

In 1975, the main Mayflower tailings impoundment washed out, resulting in the discharge of 100,000 tons of tailings and waste into Boulder Gulch and the Animas River. Considerable cleanup was required and Standard Metals, the owner of the property at the time, received a $40,000 fine for the incident, which was the largest environmental fine in Colorado’s history. In 1978, Lake Emma broke through into the 2580 Stope on Sunnyside Mine level C and flooded the mine, stripping timbers from the main shaft, crushing equipment and filling tunnels with mud. At the Gladstone portal, an estimated 5 million to 10 million gallons of water blew out the walls of the portal building. The Animas River turned black from the glacial mud and sediment well past Farmington, New Mexico.

There was an extensive legacy of manmade, systematic, and cataclysmic discharges of metals and acidity to the upper Animas River basin prior to 1985. Before the 1970s, there were no measurements of any of these discharge quantities, but they were clearly significant. Miners were not required to reclaim their sites until the 1970s and most followed the acceptable practices of their time. This massive industrial mining and milling complex resulted in enormous amounts of metals loading in the Animas River, which further limited aquatic life, including trout populations downstream from Silverton.

Standard’s permit violations included inadequate storm-water discharge control, lack of water treatment, unapproved disposal of pond sludge waste, a poorly constructed and inappropriately located waste rock dump, unapproved disposal of approximately 8,000 cubic yards of trash, failed revegetation, spring flow running through tailings ponds, and mining impacts in unpermitted areas including the Terry Tunnel and seven acres in the Sunnyside Basin, specifically the collapsed Lake Emma. Water permit violations included exceedances of cyanide, pH, zinc, total suspended solids, copper and lead discharge limits.

The water treatment facilities at Gladstone were not operating and were in such a state of disrepair that SGC had to apply for bypass approval to remain in compliance while critical upgrades were completed. The Colorado Mined Land Reclamation Division’s July 10, 1985, inspection of Standard’s operation noted the following: evident that water quality above and below the site is poor; drainage control at the American Tunnel is poor; water treatment not running; untreated water routed through ponds, then discharged to North Fork of Cement Creek; waste rock dump constructed with little engineering concern in a swampy area; sludge has been disposed at waste rock dump, trash improperly disposed. Standard Metals’ answer to these violations was to advise the regulatory agencies that Standard could not respond due to their bankruptcy filing and lack of resources.

SGC promptly brought all discharge permits into compliance, redesigned the mining operation, and completed a substantial mine permit amendment in cooperation with Colorado regulatory agencies. Specifically, SGC removed scrap iron, broken ore cars and locomotives, made drainage improvements, and constructed a new water treatment plant at Gladstone. The old dry hydrated lime-feed system was replaced with a milk of quick lime and liquid flocculent system with an effluent pH control loop. The improvements resulted in a modern, efficient operation with greatly reduced environmental impacts. As a result of SGC’s efforts, on February 29, 1988, the Colorado Mined Land Reclamation Division awarded SGC the 1987 Mined Land Reclamation Award in the classification “Most Improved Sites.” The director wrote, “Our congratulations and appreciation for the outstanding job you have accomplished.”

At the time of Standard Metals’ bankruptcy filing, Standard’s reclamation bond was only $446,100. This bond was forfeited and, through litigation and bankruptcy, th EPA recovered only $900,000 of additional insurance proceeds and some unwanted Standard Metals property that was conveyed to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The cost to reclaim the Sunnyside mine and related facilities was in the millions. Standard Metals walked away from those costs. But for SGC’s presence in the basin, the Standard Metals bankruptcy would have fit the all-too-familiar pattern of other failed mines in the West. At the Sunnyside mine, SGC shouldered all of those costs.

SGC operated the Sunnyside mine for only five years. During that time period, ore from the mine was hauled to the Mayflower mill for processing. All tailings were retained in the upper level of Mayflower Impoundment No. 4, well clear of any groundwater infiltration or surface path to the Animas River. SGC’s activities were all regulated by the federal and state governments and SGC’s activities were all permitted. The MLRD October 28, 1987, inspection report of SGC’s operations noted, “The mining operation exhibited some vast improvements over the last two years. The division would like to commend Frank Bergstrom (SGC environmental manager at the time) for his courteous, efficient and diligent manner with which he works with our office as well as in the field, as evidenced by the improvements noted, specifically at the Terry and American tunnels.”

From 1985 until 2003, SGC treated the entire American Tunnel discharge and stored the resulting sludge at the Mayflower Impoundments, even though not all of the discharge was generated from SGC property. In addition, from 1996 until 2003, SGC treated the entire flow of Cement Creek for nine months each year, removing thousands of pounds of metals from this Animas River tributary, again even though there were significant natural and third party sources of heavy metals to the creek.

During the period of SGC’s operations, the “net” load that SGC removed from the Animas was tremendous. While SGC mined additional ore, all discharges generated were permitted, treated or contained. Furthermore, SGC bulkheaded the entire mine upon closure. SGC operated the mine at a financial loss and the mine ultimately closed in 1991. SGC’s five years of mining, which used modern techniques and was under the modern era of environmental regulation, substantially reduced metals loading in the Animas River from what would have otherwise been the case.

30 Years of Reclamation and Remediation

SGC closed the Sunnyside mine in 1991

and continued the remediation and reclamation

activities it began in 1985 when

it acquired the property. SGC’s mine permit

included the notation from the Colorado

DMG that “indefinite mine drainage

treatment is not acceptable as final

reclamation. Please devise an alternate

reclamation plan.”

SGC and the state of Colorado agreed on a comprehensive watershed approach in which SGC would be released from obligations in exchange for installing engineered bulkheads to eliminate mine drainage from the Sunnyside mine workings and completing numerous other reclamation projects in the region. Many of these reclamation projects were on ground never owned or operated by SGC. This agreement was memorialized in a Colorado District Court-approved Consent Decree, endorsed by the EPA, and approved by the BLM, with all regulators noting the benefit of the watershed approach to the environment.

SGC successfully completed all tasks called for by the Consent Decree and the Colorado Water Quality Division confirmed as much on February 26, 2003. “Each criterion in the termination assessment has been successfully accomplished. Therefore, the Division has concluded that there has been Successful Consent Decree Completion.

In addition to the work summarized above, SGC has voluntarily participated with the Animas River Stakeholders Group (ARSG) to evaluate and implement projects since 1994. Using their expertise as well as a number of State and Federal agencies, the group prioritized various contributing sources to the Upper Animas based on an analysis of factors such as the amount of each contaminant, physical attributes, accessibility to power, and proximity to streams, wetlands, and avalanche paths.

Eventually, 400 sites were identified as priorities. Further analysis revealed that 67 of these historic mining sources accounted for 90% of the metals contamination from all mining sources. This comprehensive prioritization approach proved successful and led the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) to implement 27 realistic Total Maximum Daily Load standards based on partial remediation of the priority sites. ARSG implemented many of these projects using 319 grants, and SGC expenditures and participation provided a portion of the in-kind match required under that program. SGC also provided a disposal area for one of the projects.

SGC and ARSG were successful in removing 70% of the copper and 50% of the zinc in Mineral Creek. USGS analysis concluded that the “remediation project ... resulted in long-term reductions of the copper concentration and significant improvement in copper load in Mineral Creek. A similar reduction in zinc (and cadmium) concentrations is also evident.” SGC’s 30 years of remediation and reclamation substantially reduced ongoing metals loading in the Animas River from what would have otherwise been the case.

Metals loading in the Animas River is the result of the geologic setting and more than a century of historic mining in the area. The Silverton Caldera is highly mineralized, and acid rock drainage and poor water quality in the area was always prevalent given the natural generation of significant quantities of heavy metals.

There was also an extensive legacy of man-made, systematic, and cataclysmic discharges of metals and acidity to the Upper Animas River basin prior to 1985. It is incontrovertible that both SGC’s five years of mining between 1986 and 1991, which used modern techniques and was under the modern era of environmental regulation, and SGC’s 30 years of remediation and reclamation in the Silverton Caldera each substantially reduced metals loading in the Animas River from what would have otherwise been the case. But for the actions of SGC, metals levels in the Animas River, and the resulting impacts on aquatic life, including the trout fishery downstream of Silverton, would undoubtedly be more adverse.

Steven Lange is the director of the Geochemistry, Groundwater and Surface Water Group at Knight Piésold USA. He brings more than 40 years of experience related to investigation, evaluation, and remediation of mining and industrial sites throughout the world. He has conducted baseline environmental studies, geochemical evaluations, ARD assessments, and geochemical modeling for feasibility, operational, closure, and remedial investigation studies at mine sites around the world. He has been studying and evaluating mineral deposits in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado since 1976. This article was adapted from a technical paper he authored. The full version can be found at www.sgcreclamation.com/reports/ miningandrec.pdf.

SGC’s Primary Reclamation Activities:

Historic Mayflower Impoundment No. 1—SGC moved the impoundment

toe back from Boulder Creek and the highway to minimize

the potential for erosion and migration. SGC flattened the

side slopes to increase stability and potential for revegetation,

regraded to promote drainage, capped with subsoil and seeded.

Historic Mayflower Impoundment No. 2—SGC moved the impoundment toe back from Boulder Creek to minimize erosion and migration potential. SGC flattened the side slopes to increase stability and the potential for revegetation, regraded the top to promote drainage, capped with subsoil and seeded.

Historic Mayflower Impoundment No. 3—SGC regraded the top to promote drainage, capped with subsoil and reseeded.

Mayflower Impoundment No. 4—SGC excavated and relocated approximately 80,000 tons of mostly historic mine waste and historic tails to Mayflower Impoundment No. 4, regraded the area and re-seeded. SGC improved the intercept and diversion drains and placed a concrete diversion wall to divert groundwater to surface and around the tailings material. SGC also installed a lined toe ditch.

Mayflower Mill Area—SGC cleaned the site, contoured and seeded. SGC ultimately donated the mill to the San Juan Historical Society along with $120,000 and nearby property. The mill is now on the National Register of Historic Sites and operated as a historical tour by the San Juan Historical Society.

Eureka Tailings—SGC removed 112,000 yd3 of historic finely ground tailings, which are more geochemically active, from the banks and floodplain of the Animas River and its tributaries and relocated them to the Mayflower Impoundments.

American Tunnel mine waste and tailings—SGC removed 80,000 tons of mostly historic mine waste and tails.

Longfellow-Koehler Project—SGC opened a caved adit and removed 32,000 yd3 of mine waste and pond sediments, consolidated other waste to reduce footprint, added neutralizing materials to the area, covered the area with overburden, seeded, and constructed surface water diversion to divert upland flow around the site.

Boulder Creek Tailings—SGC removed 5,700 yd3 of tailings from the Boulder Creek and Animas River flood plain.

Pride of the West Tailings—SGC excavated 84,000 yd3 of historic tailings and relocated 45,000 cubic yards to an on-site tailings impoundment and the remainder to the Mayflower Tailings Impoundment No. 4. SGC conducted a geotechnical study, installed a toe drain and contoured to the slope. SGC capped the impoundment with overburden, fertilized and seeded. SGC partially rebuilt and planted a wetland.

Lead Carbonate Tailings Impoundment Removal—SGC relocated 27,000 yd3 of tailings to Mayflower Impoundment No. 4, regraded, neutralized and reseeded the area.

Lime injection—SGC injected approximately 1.3 million lb of hydrated lime into the interior workings of the Sunnyside mine to increase alkalinity.

Gold Prince Mine Waste and Tailings—SGC installed two closure bulkheads, relocated historic tails and ash piles into lined containment within a consolidated waste pile that was relocated away from stream flows, covered removal areas with overburden, and seeded.

Ransom adit drainage—SGC opened the caved in adit, designed and installed a bulkhead to eliminate drainage, graded the portal area, and seeded.

Mayflower Hydraulic Controls—SGC designed and installed three interception structures to capture and transport stormwater and groundwater around Mayflower Impoundment No. 1 and the Mayflower Mill area to prevent contact and infiltration with tailings and waste rock.

Sunnyside Basin—SGC placed 240,000 yd3 of clean fill to cover the Lake Emma subsidence area and to create positive drainage, contoured the area and seeded.

American Tunnel portal—SGC removed surface facilities, constructed a diversion ditch, stabilized the bank of Cement Creek, recontoured and seeded.

Mogul adit and Koehler Tunnel Bulkheads—SGC funded the placement of bulkheads in the Mogul Adit and Koehler Tunnel.

Mayflower Passive Treatment Wall—SGC constructed a passive treatment wall for groundwater, leaving a wetland near the southwest corner of the historic lower deposits in Tailings Impoundment No. 4.

Power Plant Tailings—SGC picked up tailings previously reclaimed along the Animas River in the vicinity of the old power plant and consolidated these into Tailings Impoundment No. 4.

Bulkhead Installation—With oversight and approval of all relevant agencies, between 1992 and 2002, SGC installed a series of nine engineered concrete bulkheads in the Sunnyside mine, and the Terry and American tunnels to isolate the mine workings from other workings in the area and to prevent water flow from the Sunnyside mine workings into the Animas River. The bulkheads were always expected to return the local water table toward its natural, pre-mining level.