Tracing Copper’s Future:

Chile’s Changing Priorities

Price bull commentary steals the limelight from real growth challenges and responses

By Jesse Morton, Technical Writer

The national economic backdrop is sustained, albeit slow, growth. The country’s central bank reported economic activity rose 1.6% in 2017. It announced it anticipates an uptick in investment following the election of Sebastian Piñera, who will take office in March. Piñera, in his second stint as president, is expected to deliver on promises to cut the corporate tax rate and roll back his socialist predecessor’s tax, labor and education reforms. Among his promises is the target of a 7% increase in investment, presumably by private sector players.

Shortly after the November election, headlines surfaced revealing Chile had dropped from 48th in 2016 to 57th in 2017 out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s “Doing Business” competitiveness rankings. The World Bank said the rankings are based on hard data, such as tax rates and legislation passed.

More recently, the central bank reported a trade surplus of $1.21 billion in January, a 7% increase year-over-year. Traders polled reported expecting the bank to hold its benchmark interest rate at 2.5%; and inflation is expected to remain stable.

Also, in January, Chile’s senate president visited China for bilateral talks on boosting economic cooperation. China currently represents up to 50% of the global demand for copper, depending on the source. Demand there for electric vehicles, which use four times the amount of copper as traditional vehicles, is expected to increase demand for both lithium and copper. Further goosing copper imports to China is the Made in China 2025 program, which involves the widespread adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in the country’s manufacturing sector, and the government’s crackdown on the importation and circulation of copper scrap. Traders are now blocked from importing it if they cannot prove they are the end-users.

Both could fan the flames of already strong demand. Copper prices increased 39% in 2017 to tap a four-year high of $7,259 per metric ton (mt), or $3.30/ lb. Goldman Sachs projects continued growth in prices, with prices expected to climb 12% to $8,000/mt, or $3.64/lb, in 2018, a price not seen since 2013. On the basis of such headlines, Freeport Mc- MoRan’s CEO reported during an earnings call that “commentary” on copper price and production outlook “is as positive right now as we’ve seen.”

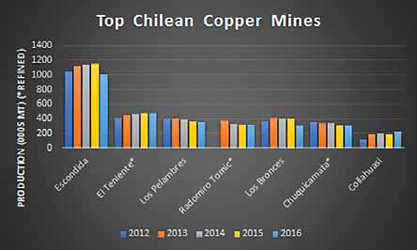

Feeding that commentary, many of the majors are either reporting and/or forecasting increased production. Codelco, Chile and the world’s topmost copper producer, forecast a total production increase of 100,000 mt, or 6%, coinciding with a cost-savings increase of 46% through 2019.

Rio Tinto reported it could mine 610,000 mt in 2018, an increase of 28% over its realized 2017 production of 478,100 mt. It reported its forecast 2018 output could hit 265,000 mt, a 34% increase year-over-year.

Representing the juniors for the purposes of this article, Antofagasta and Amerigo both reported increased copper production in 2017. In its third-quarter highlights, the former reported production was up 4.5% over the same timeframe for 2016. “In 2018, we plan to increase production to 705-740,000 mt of copper as Encuentro Oxides ramps up to full production,” Iván Arriagada, CEO, Antofagasta said.

Amerigo reported a breakout year, increasing annual production by 10% in 2017, a boon from processing plant equipment upgrades at the company’s Cauquenes tailings deposit operation. “We plan to have another record year in 2018,” Rob Henderson, CEO, Amerigo, said.

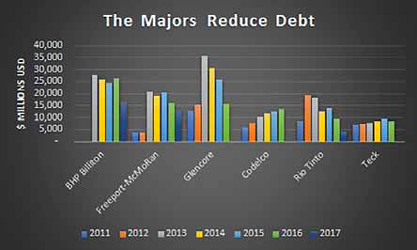

Chile’s Comisión Chilena del Cobre (COCHILCO) reported the country’s copper production in 2018 could top 5.74 million mt, an increase of 271,000 mt, or 4.9%, over the 5.47 million mt produced in 2017. “This growth is mainly explained by a rebound in production at Minera Escondida, which recovers its level, achieving a little more than 1.2 million tons, after the 2017 fall,” Paula Maldonado, COCHILCO spokeswoman, said. “The increase in Antucoya and Sierra Gorda will also be relevant.” The ministry forecasts year-over-year growth through to 2027, which will see a 13.9% increase in production over 2016, she said.

That said, increased Chilean and indeed global production will fall short of meeting the anticipated demand this year, COCHILCO reported. The resulting supply deficit could drive prices. It reported expecting the supply deficit to hit 175,000 mt in 2018, compared to a deficit of 67,000 mt in 2017. This is due to an uptick in demand from China. “We estimate that in 2018, worldwide refined copper from scrap processing would register a fall of 5.5%, which would impact on a higher demand for copper concentrates,” Maldonado said. “On the other hand, the demand for copper in the world, excluding China, would recover growth with a 1.5% rise compared to the zero figure in 2017.”

Indeed, as Goldman Sachs and others have pointed out, a net supply deficit should favor growth in the Chilean copper sector. Headwinds, however, cannot be said to be nonexistent. Energy and labor costs could challenge forecast timelines and planning at some of the bigger operations. And quantitative tightening, planned for this year, by the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan could squeeze liquidity in the global economy and prompt some of the bigger miner’s to further eliminate debt and reconsider certain expenditures.

Thus, while price bulls are making headlines, the picture for growth in the sector in Chile is somewhat cloudier. For starters, while COCHILCO anticipates national copper production to increase this year and, more specifically, through 2026, that hinges on almost three dozen new and expansion projects launching in the next half decade or so. It is also dependent on the roughly two dozen organized labor negotiations calendared for 2018 progressing smoothly and not disrupting operations, production and the long-term plans of the employers. This will be covered later.

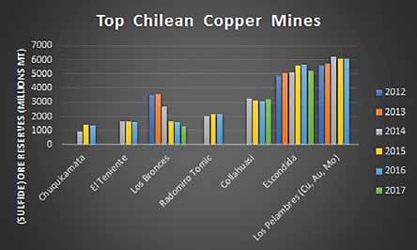

Additionally, rising prices and demand will run up against declining grade at some of the bigger mines in Chile. Previously, Escondida’s numbers have been subject to grade-adjusted revisions. It is a similar story for Codelco’s Chuquicamata and Radomiro Tomic. “The mining industry faces endogenous challenges not only of lower ore grades, but also deposits that are more complex and higher operation costs due to the need of deeper mineral exploitation,” Víctor Pérez, manager, business planning and market development, Codelco, said.

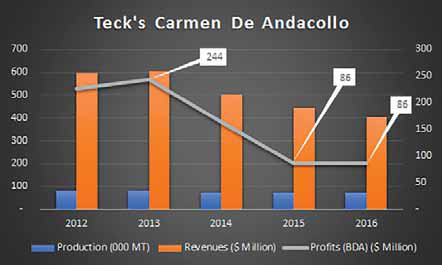

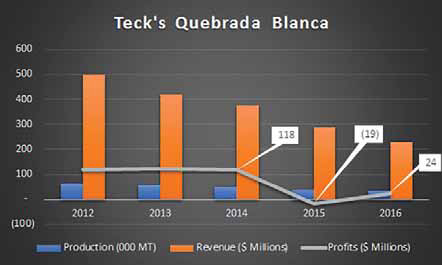

A solid example is Teck, which faces a mix of challenges that include tough decisions regarding optimizing use of existing infrastructure to offset levitating costs and manage declining grade. Over the last half decade, the miner has logged declining production, revenues and profits at both its operational Chilean copper mines, Quebrada Blanca and Carmen de Andacollo. Teck reports the supergene at the former will effectively be exhausted in 2019. The latter features what Teck describes as “gradually” declining grade.

Starting in Q1 2017, Quebrada Blanca ore was put through a dump leach circuit, which resulted in “lower recovery and a longer leaching cycle at reduced operating costs compared to the previous operations of the heap leach circuit,” the company reported at the end of Q3. Most importantly, that saved money, but “copper production in the third quarter decreased to 5,100 mt compared with 8,600 mt a year ago.”

At the Carmen de Andacollo, Q3 copper production of 19,700 mt was similar to that of the same time last year, but “improved grades were offset by lower mill throughput,” the company reported. These moves saved the company $19 million for the quarter year-over-year, “primarily as a result of suspending the crushing, agglomeration and stacking circuits associated with the previous heap leaching operation,” but contributed to an enterprise-wide 10% decline in annual copper production.

Teck is reportedly advancing the Social and Environmental Impact Assessment regulatory approval process for Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 (QB2), which will have an initial mine life of 25 years and annual production capacity of 300,000 mt for the first five years, the company reported. “A decision to proceed with development will be contingent upon regulatory approvals and market conditions, among other considerations,” Teck reported.

The meaning of that statement perhaps broadens in light of the eight-day strike that occurred at Quebrada Blanca in December. The previous collective bargaining agreement expired at the end of November. At that point, workers initially stumped for a bonus scheme and when that failed put down their tools. The result was a 24-month contract. Teck reported the strike did not impact production.

The company is not among the majors that have routine labor negotiations scheduled for 2018, but will return to the table in 2019 at Carmen de Andacollo. The Quebrada Blanca strike was one of three in Chile in a single seaon. Workers at Escondida struck after layoffs in late November. And negotiations failed and the government planned mediation efforts in early January at Glencore’s Lomas Bayas mine after workers there rejected a contract offer.

Prior to those, a 44-day strike at Escondida in Q2 2017 was blamed for an 8.6% decrease in mine output, a 21% year-overyear decline in refined copper output by Rio Tinto, global copper price increases, and the aforementioned decline in national annual copper production.

That strike has been referenced by copper price bulls when discussing the more than two dozen labor negotiations scheduled for 2018. “The main negotiation foreseen for 2018 would occur at Minera Escondida, from BHP,” Maldonado said. “It should be noted that this negotiation had to be carried out in 2017; however, it was suspended for not reaching an agreement by the legal deadline.” Due to the “dismissal” of 122 employees there in November, “it is the most complex negotiation of 2018.”

Codelco will field a whopping 14 collective renegotiation contracts in 2018. “We have the challenge to sit down and negotiate with our workers in the middle of an upward trend of copper prices,” Pérez said. “Moreover, we have to deal with a new labor legislation that, among other things, obliges the last collective contract to be the floor of the negotiation,” he said. “It will not be easy, but we must ensure that our workers remuneration packages are correlated with their productivity.”

However, copper price bulls may be disappointed if they are counting on labor negotiations to cascade into severe production disruptions, Maldonado said. “Chile is a country with low labor conflict in mining,” she said. For example, in January, state-backed Codelco quietly secured a labor contract at Andina, and the Lomas Bayas negotiations ultimately fruited into a contract deal with 90% of the workers buying in.

Potentially ballooning labor costs are not the only headwinds to growth in the sector. Energy and credit costs both threatened to break out in Q4 2017. As oil topped $70 a barrel, Antofagasta reported it anticipated cash costs before byproduct credits to tap $1.65/lb, a 3% increase. Fuel costs can account for as much as 30% of costs for some miners, and, while opinions vary, some analysts see unit costs increasing by as much as 10% in 2018.

Those costs could rise at a time when the world’s foremost central banks are raising rates and the Federal Reserve is trying to incrementally jettison the $1 trillion in bad bets it bought during the 2008 stock market crash. The Fed is forecast by many to raise key rates thrice in 2018. And as late as Q4, 2018, it will start clearing its bailout balance sheet, reportedly to the tune of $10 billion per month.2 Needless to say, this could introduce both volatility and a tightening of credit in the system. (For an example of what quantitative easing [QE] did, look at the American stock markets for the past half-decade. And consider the Fed is planning to start doing the opposite of QE this year. It has been since Greenspan was Fed chair [1987-2006] that the real interest rate was not negative.)

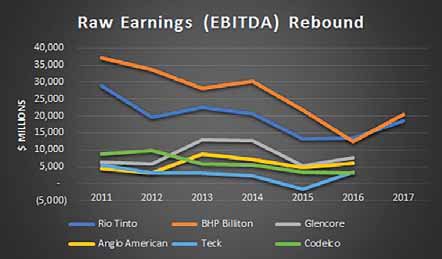

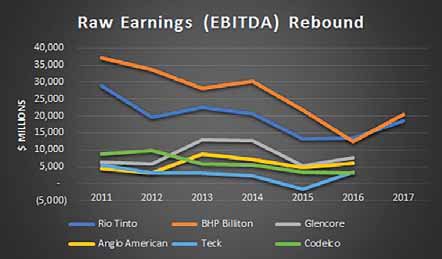

However, that picture is incomplete. First, many of the majors are better capitalized now than they have been in some time, thanks to debt-elimination programs. Additionally, the majors have seen raw earnings rebound somewhat since 2015 lows. While debt elimination may have been in response to and in anticipation of rising interest rates, better capitalization means they are in a better position financially to squeeze the trigger on large purchases. It also means they are positioned to deal with unions. One example would be Capstone Mining, which reduced its debt by almost 20% and increased its revenues by more than 25% in 2016. The company, which currently has mothballed exploration at its Santo Domingo property, which is primed for $2.85/lb copper, reported it has built Chile’s labor negotiation cycle into the feasibility study and long-term plans for the site. “We probably scoped it at relatively high wage rates,” Cindy Burnett, vice president, investor relations, said. “We’re seeing wages move up through our business. It is not a given that it will have a significant impact.”

Second, North American shale gas and oil sands may keep some energy prices low. Further, symbolically, Chile’s being on increasingly better terms with its energy-rich neighbors bodes well for the future. For example, since the 2014 ruling by the International Court of Justice on contested territories between the two countries, relations have improved between Chile and Peru, now free trade partners in the Pacific Alliance. Beyond removing 70% of the land mines placed on the shared border, the two are constructing a 30-mile electricity transmission line starting this year with completion set for 2019. The line has a meager 200-megawatt capacity, but, if successful, could boost plans for another line between the Camisea gas project and the city of Antofagasta.

Now the court is set to settle a dispute between natural gas-rich Bolivia and Chile. When the dots are connected, the picture that emerges is of a sector in transition. This year could spin one of two narratives. Limited global supply and burgeoning demand result in higher prices that universally lift production and accelerate new mine and mine expansion projects nationwide. Or, the threat of increasing labor and energy costs jibe with global quantitative tightening, which, by Q4, tempers demand and feeds only asymmetrical growth.

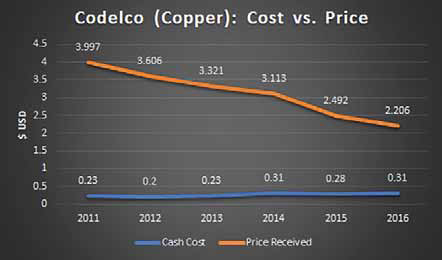

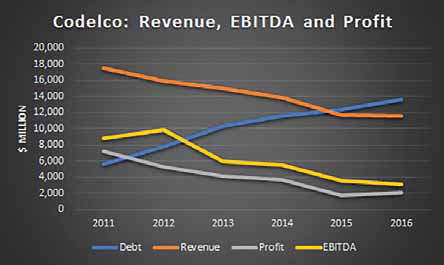

One indication that vision has legs is Codelco’s traceable copper program. Over the last half decade, Codelco has seen cash costs per pound increase while the price received has decreased. It has seen debt eclipse revenue and raw earnings decline for four straight years. Revenue in 2016 was down 34% from 2011. The company faces the same emergent challenges beginning to define the sector. One answer was the 2018 announcement of its Responsible Copper Initiative, which, it reported, in the long run could de-commoditize the red metal. The initiative will involve strategic partners, nongovernment organizations, copper consumers and producers, Codelco reported. So far, the company has signed agreements with BMW, Mitsui & Co. and Nexans. The idea is to have an external source certify copper cathodes on carbon footprint, water footprint, territorial impact, community impact, human rights, equal opportunity and inclusion, occupational safety and health, transparency, ethics, and traceability of funds. “The goal is to have an integrated value chain where final products can be fully traced,” Pérez said.

The company reported the demand for traceable copper initially came from smelters, predominantly in China. Increasingly, the demand for “traceable products is not limited to the mining or copper sector, instead it is a trend that is being identified across a number of industries,” Pérez said. “To give you an example, electromobility, a sector that demands environmentally friendly produced copper, will demand 1.74 million mt in 2027 compare to the 185,000 mt that this sector is currently demanding,” he said. “This means, that just this sector will demand an amount of traceable copper equivalent to Codelco’s annual production.”

The move obviously reflects the optimism of the price bulls. Demand is anticipated to be so high going forward that generating more expensive product will be economically viable. It also reveals an emergent philosophy at a state-backed company in a country with powerful unions, a general trend in declining grade and potentially rising costs. If Saudi Arabia granting women the right to vote and drive is any example, then when the winds of fortune shift so too shift priorities. “Success is to be the market leader when defining good practices, respect for our workers, diversity, equality of conditions and human rights, care for local communities where we operate, and efficiency in the processes, but also for being best-in-class in sustainable practices,” Pérez said. “Of course, traditional indicators are also very important.”