Dr. Norman Keevil’s 2017 book tracks the

rise of Teck Resources and summarizes

a century of mining in Canada.

(Image: McGill-Queen’s University Press)

Prospectors and Developers Beware

After reviewing a century of Canadian mining in his new book, Teck Chair Norman

Keevil tells E&MJ two lawsuits shed light on the legal implications of seemingly

mundane exploration contract negotiations

By Jesse Morton, Technical Writer

One that speaks to exploration crews and geologists is the topic of avoiding litigation that can arise from coordinating prospecting efforts with other companies, hunting so-called elephants, and trying to lock in contracts. Keevil’s book spends a few dozen pages covering a couple of lawsuits spawned from exploration and development contract negotiations turned sour. In them, the courts are forced to decode industry norms and officiate seemingly informal negotiations that are typical for the sector. “These things come up all the time,” Keevil said. “In the business, you get people doing high-risk deals and you don’t have an army of lawyers,” he said. “And you shouldn’t have an army of lawyers on every high-risk deal because you’d be paying the lawyers more than you pay for drill holes.”

This means that in many cases, a geologist has to double as an amateur lawyer, he said. “It is not easy because none of us are trained to do that,” Keevil said. “So, two exploration geologists decide on a deal and 999 times out of 1,000 there is no discovery,” he said. “But when there is one you look back and say, ‘holy smoke, why didn’t I do this right?’”

In one such major case, it took years of litigation before the Supreme Court of Canada sorted it out.

Corona v. Lac

Gold was first struck near Hemlo, Ontario,

in 1929. Claims were staked after World

War II. One of the claimants, “a Dr. Williams,”

secured a title for a property and

“did some exploratory drilling in 1947,”

Keevil wrote. Among other prospectors

plying the area, Teck Hughes did some

drilling near the Williams property in

1951, finding “nothing interesting” at

the low gold price of the day.

Decades later, International Corona Resources Ltd., a publicly listed junior mining company, staked a claim and got permission to do some exploratory drilling in the same area. “The early, near-surface results were similar, narrow, and not particularly high grade in gold,” Keevil wrote.

By the spring of 1981, Corona had drilled 75 holes at a cost of roughly $2.5 million. “Corona had only found narrow zones that didn’t appear to be economic to mine,” Keevil wrote. The 76th, and deepest, drill hole by geologist David Bell “hit pay dirt.” The economic ore apparently ran beneath the surface mineralization.

Corona published some of the results as news releases and in newsletters, which got the attention of Lac Minerals Ltd. The latter visited the property on May 6, 1981. There, Lac viewed confidential documents, to include maps, assay results and drill plans, and was advised of the estimated potential of the deposit. Bell shared his theory that that the deposit was strata- bound. “He thought it might be volcanogenic, genetically related to the original volcanic activity that laid down the rocks in which it occurred,” Keevil wrote. And the favorable rocks apparently extended west, under the Williams’ property.

Separately, University of Calgary professor, Peter Bowal, in a review of the case for Law Now, reported, “Lac advised Corona to pursue the Williams property.” Lac proposed a joint exploration agreement. Corona wasn’t ready for a deal, Keevil wrote. “They were having too much fun exploring, but each side agreed to keep in touch.” Bowal reported, “No confidentiality measures were discussed at this meeting.” Similarly, the Supreme Court reported, “The matter of confidentiality was not raised.”

After the meeting, Lac acquired government maps and land ownership data, Bowal reported. “Lac geologists determined that about 600 claims should be staked in the area and immediately began staking claims.”

A couple of days later, the companies met at Lac’s headquarters, reported Bowal. “The geology of the area was further discussed along with potential high-level terms of an agreement between the two companies,” he reported. “Lac followed up with a letter describing various options on how Lac could partner with Corona to exploit the resources on Corona’s land.” Lac reportedly proposed partnering with Corona on the overall Hemlo deposit project. “Lac would finance it, and create a subsidiary to form a joint venture with Corona to develop the property,” Bowal reported. Roughly at that time, more assay results were being published. “Corona never imposed confidentiality on the information it was sharing with Lac,” Bowal reported. “Likewise, Lac never said it would not purchase the property.” These types of maneuverings, however, are par for the course.

Afterward, a Corona representative tracked down the Williams widow in the U.S. and made an offer. While that offer was being considered, exploration continued. Corona “suspected that there might be competition from another company, and in July, Corona sent a further offer directly to Mrs. Williams,” Keevil wrote. “However, it turned out that Lac had also approached Mrs. Williams for its own account, and in late July she agreed to sell the property to Lac.”

Looking back, Keevil said, Lac may have been acting on a lack of confidence in Corona to acquire the property and on the presumption that if they didn’t make a move, someone else would. Corona “didn’t have a bunch of land men and lawyers” to micromanage the purchase, he said. Beyond that, Lac may have sensed the Corona representative was either “dealing for himself” or that he would blunder and lose it to an aggressive third party, Keevil said. “So, they decided to preempt that and go and get it themselves,” he said. “Had they done it for Corona, there would have been no issue, but they did it for themselves. That is where the issue was.”

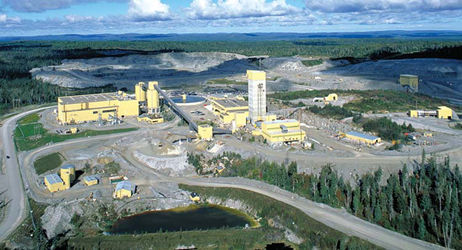

Corona sued for breach of contract, confidence and fiduciary duty. Thereafter, Corona signed Teck on a development deal and the latter began drilling. “Teck had calculated geological reserves of 1.3 million tons of 0.3 oz of gold per ton,” Keevil wrote. “The deposit could be a major discovery.”

Lac then announced a deposit of 1.8 million tons at 0.175 oz of gold per ton on the Williams property, Keevil wrote. “Lac decided to place the property into production at a rate of 6,000 metric tons per day (mt/d). They would take their chances on the trial.”

Lac then incrementally upped investment in the site, Bowal reported. “Lac had spent about $204 million to develop the mine, but by the beginning of 1986, the Williams property was estimated to be worth $700 million,” he reported. “This would rise to $2 billion by 1994.”

Meanwhile, the courtroom proceedings weren’t going well for Lac, a reality that was only apparent to those who were actually in the courtroom following the action, Keevil wrote. Eventually, Lac’s president met with Keevil, with the latter prepared to settle. The former didn’t appear open to the idea, Keevil wrote. “He was polite, but I’ve never seen anyone so nervous.” Another meeting was planned but fell through.

The judgment was handed down on February 3, 1986, after the markets had closed for the day, and almost five years after the fateful 76th hole was drilled. The judge sided with Corona. “It would not be over for another three years until Lac exhausted its appeals,” Keevil wrote. “Six more judges at the Ontario Court of Appeal unanimously upheld Mr. Justice Holland’s decision later that year.” From there it would go to the Supreme Court of Canada.

There the justices unanimously upheld the ruling of a breach of confidence by Lac. It held that confidential information “was shared by Corona under the assumption that there would be a business arrangement or joint venture between the two companies in the future,” Bowal reported. “Lac had exploited this confidential information for its own gain, at the expense of Corona.”

Summarizing the view of the court, Justice Gérard Vincent La Forest wrote, “The practice in the industry was premised on the disclosure of confidential information in the context of serious negotiations and was so well known that at the very least Corona could reasonably expect Lac to abide by it.” The practice was both clear and common knowledge, he wrote.

The court “imposed a constructive trust on Lac for the benefit of Corona, which was essentially to give Corona the mine,” Bowal reported. Teck ultimately took a 50% stake in the mine, which went on to become “Canada’s top gold producer,” he reported. “In the first quarter of 1990, the mine produced more than 151,000 oz of gold. Three mines eventually arose from the Hemlo lands and total production was 1,058,000 oz of gold.”

Lac was later taken over by Barrick, which also acquired Corona on its way to becoming the biggest gold miner in the world. The case proved to be an oft-cited landmark ruling regarding corporate morality. A breach of confidence is determined by, among other things, industry norms for information sharing. However, it left unclear as to at exactly what point do contract negotiations impose fiduciary obligations. Despite the letter, the proposal and the meetings wherein fiduciary relationships were being discussed, none could be said to exist at the time Lac made its move, according to three Supreme Court justices. “These things are never that clear,” Keevil said. “I am not a lawyer.” He did say, however, that some clarity might be found in an earlier case that indirectly impacted Teck.

Leitch v. Texas Gulf Sulphur

In 1959, Texas Gulf Sulphur (TGS)

launched an aerial exploration campaign

covering the Abitibi region of the Canadian

shield. It was initiated by geologist

Walter Holyk, “who was one of the earliest

proponents of the then-new volcanogenic

theory of the origin of many base metal

mines,” Keevil wrote. “Holyk had worked

in New Brunswick, where some large deposits

of that type had been discovered,

and had concluded that similar opportunities

might occur in the Abitibi region of

Ontario and Quebec, stretching from Timmins

to Mattagami.”

The campaign was waged from the company’s helicopter-mounted electromagnetic sensor system. The operators would routinely test the system over a “small rock outcrop in the Kidd Township, 20 kilometers north of Timmins,” Keevil wrote. “The lore has it that the Kidd Creek anomaly they used as a test case was so strong that it was thought it must be caused by graphite,” he wrote. “For that reason, TGS never tested it by drilling early in the program, even as it was flown over and used to calibrate the survey equipment first thing every morning.” Another account, “probably more accurate,” is the company couldn’t gain access to the property for four years while it negotiated with the owners; however, it “could fly over and test it from the air with impunity.”

The helicopter was used to AEM-survey “large swaths of Northern Ontario and Quebec” before it “crashed” and was “scuttled,” Keevil wrote. “TGS discovered countless anomalies, which is one of the hidden difficulties of owning one’s own airborne geophysical system.”

Follow-up costs can dwarf the original survey costs. Thus, around this time, TGS contracted Leitch, “a small exploration company run by one of the icons of the Canadian exploration industry,” Karl Springer, to review the airborne EM data and follow up, Keevil said. “Then they drew the contract up on a piece of paper and they had a map sketched in by hand.” The contract held that “should Leitch make a discovery on property in the new joint venture area, the two parties would share in it, with TGS holding a 10% interest and Leitch holding 90 per cent,” Keevil wrote.

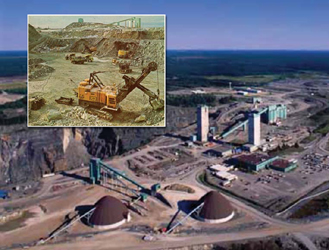

TGS drilled 65 anomalies in Ontario and Quebec, and then the funds started to dry up. “Project geologist Ken Darke in Timmins was told to cease and desist from more foolish drilling,” Keevil wrote. By then, negotiations with the Hendrie Estate had resulted in TGS being allowed to drill the Kidd Creek anomaly. “In November 1963, Darke drilled a hole named Dragon 66, after the year of the dragon and the fact that it was the 66th and last anomaly to be drilled before the project really shut down,” Keevil wrote. “It encountered 200 meters of high-grade copper and zinc mineralization, running over 1% copper and 7% zinc, and contained significant values in silver as well.”

The deposit would prove to be “the largest base metal ore body of its type ever found in Canada,” Keevil wrote. TGS initially stayed mum while it locked in more pertinent properties. Charles Fried, in his book Contract as Promise: A Theory of Contractual Obligation, wrote that the mineral rights cost TGS a total of $18,000, and the property was estimated to be worth $100 million. But “diamond drillers and geologists talk,” Keevil wrote. Rumors, frenzied stock purchases, and accusations followed.

According to the Securities and Exchange Commission, TGS leadership and employees acted quickly on assay results by buying up company stocks and then sending out a press release on April 12, 1964, that served to quell rumors of a big discovery. Three days later, official drill results were announced, the news of which didn’t hit the public until the next day. According to the SEC, TGS insiders continued to purchase stock between the April 12 and April 16, which resulted in the court handing down a conviction for insider trading. “Defendants should not act upon the information until the information is disseminated to the point that the public would have had a reasonable opportunity to act on it,” Case Briefs reported.

Synchronously, Leitch tried to claim the site of the anomaly, referencing the contract and map. “You could say that that discovery anomaly was either on the ground that they talked about or on the ground that Texas Gulf had asked to keep,” Keevil said. “It was just a squirrelly line in pencil.” TGS balked. Leitch sued over breach of contract.

The case hinged on the contract and map. In the book, Judging Bertha Wilson: Law as Large as Life, about the Canadian supreme court justice who earlier in her career was on the law firm that represented TGS, author Ellen Anderson described the case as “extremely complex.” Leitch argued that “the contract and the location maps incorporated within it were both ambiguous in key respects.”

In court, however, it came down to the believability of the testimony, specifically regarding “verbal modification of the contract,” Anderson wrote. Closing arguments spanned 23 days total. “It could not have been an easy decision, and Mr. Justice George Gale took seven months to prepare his judgment, in the end concluding in favor of Texas Gulf,” Keevil wrote. “His key finding was that, wherever Leitch Geologist Charles Pegg’s recollections and statements differed from Holyk’s, the judge chose to accept Holyk’s.” Anderson wrote that the judge held “there was not patent ambiguity and no relevant latent ambiguity in the contract.” Apparently, the TGS lawyers were able to sway the judge. “The remainder of the case turned on credibility.”

The judge’s opinions were deemed findings of fact, making them almost impossible to overturn on appeal. It is believed Wilson was hinting to this case in a speech to rookie trial judges when she said, “Appellate courts may be able to overrule you on the law, but on the facts, you, the trial judge, are supreme. … The real challenge is finding the right facts, the facts that are going to paralyze the judges on appeal and leave them gnashing their teeth in frustration.”

Perhaps to avoid such gnashing, Leitch never did appeal the ruling. One of the morals of the stories, Keevil said, is to be sure to accurately document negotiations as they unfold. “If you do a joint venture, take care to make sure you’ve got it properly documented,” he said. “In the Leitch case, they had an agreement, they had a joint venture, but the agreement was vague.”

In the book, Keevil wrote, “Handshake deals done in the field, with the best of intentions, can come unwound after one side becomes highly successful, seemingly at the cost of the other.” A deal may arise in informal circumstances. The Leitch contract was drafted in the relaxed environs of the engineer’s club. The meetings between Lac and Corona were so informal as to go undocumented. In both cases, a lawyer could debate either way as to the seriousness of the business proceedings accomplished at either.

“This is common in the business,” Keevil said. “Two exploration geologists or landmen get together at a property and start talking about doing something together, and it doesn’t always work as precisely as we might want to think in hindsight,” he said. “So, if you are going to make a deal, ideally put it on paper as quick as you can, but be clear enough about it that nobody is going to overturn it.”

That means don’t pretend a handshake will be enough. The reverse, however, is also true. Don’t pretend handshakes don’t matter, because they do. “A handshake is only as good as the hand attached,” he said. Ergo, to maintain rapport and avoid litigation, the best practice “is if it doesn’t feel right don’t do it,” Keevil said. “The corollary to that is the old golden rule, do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” That rule doesn’t need a judge to clarify it. “We’re all trained on that by our old ladies as we’re growing up.”

While the Corona v. Lack trial was heavily watched by players in the sector, the impact of its ruling on contract negotiations was marginal, Keevil said. “You would hope it would change after that,” he said. “I haven’t seen any evidence that it has changed one way or another.”