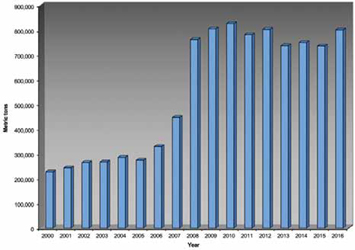

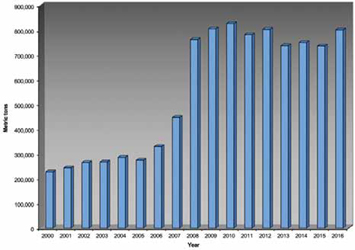

Figure 1—Iceland’s aluminum smelter output, 2000-2016 (mt). Source: British Geological

Survey apart from 2016 production: USGS estimate.

Nordic Miners Mark Time

From the boom days of just a few years ago, the Nordic mining scene has

essentially retrenched to its established structure as more speculative ventures

have found the going too tough. That has not stopped innovation, however,

particularly in the region’s metallurgical sector.

By Simon Walker, European Editor

The relative inactivity compared to four or five years ago, for example, has nothing to do with the region’s mineral potential: far from it, in fact. Much more to the point is that exploration funding has shrunk worldwide, especially for the junior sector, while the relatively high production costs inherent for mines located in countries with expensive labor, strong environmental-protection policies and challenging infrastructural logistics has unquestionably hurt existing producers’ competitiveness.

Iceland’s Energy Conundrum

Although without its own mining sector,

metallurgy — particularly aluminum

smelting and other high-energy processes

— is a significant contributor to Iceland’s

economy. The country generates around

85% of its primary energy needs from renewable

resources, with hydropower contributing

20% of the total. And this abundant

hydropower has been the key to the

success achieved by Iceland’s aluminum

smelters, with the country today hosting

three plants with a combined annual capacity

of some 800,000 metric tons (mt)

of metal. Development in Iceland’s aluminum

smelter output since the start of the

21st century is shown in Figure 1.

In operation since 1998, Norðurál’s Grundartangi smelter is currently involved in a long-term expansion project aimed at increasing annual capacity from 280,000 mt to around 325,000 mt per year (mt/y) in due course. Its nameplate capacity in 2016 was 313,000 mt/y. Operated by a wholly owned subsidiary of U.S.-based Century Aluminum, Grundartangi produces standard-grade aluminum and a primary foundry alloy product. It is also Century’s largest, most modern and lowest-cost smelter.

The plant operated at full capacity during 2016, in contrast to the company’s three U.S. smelters, only one of which ran at capacity last year. Commissioned 10 years later, Alcoa’s Fjarðaál smelter has a nameplate capacity of 344,000 mt/y. The company did not identify the output of individual plants within its overall metal total in its latest annual report, but the assumption must be that Fjarðaál’s low energy costs will have allowed Alcoa to run the plant at or near full capacity. The company claims that Fjarðaál is one of the world’s most technologically advanced plants, with a low environmental footprint that is helped by the use of a flue-gas scrubber that removes a reported 99.8%-plus of the smelter’s emissions.

The smallest of the three Icelandic smelters, Rio Tinto’s wholly owned ISAL plant at Straumsvík produced its nameplate 205,000 mt of metal last year, marginally higher than in 2015. Located at Hafnarjordur, it is also the oldest of the three, having been commissioned in 1969.

As the principal power producer in the country, Landsvirkjun is a major player in Iceland’s aluminum industry. In May 2016, the company extended its supply agreement with Norðurál Grundartangi for a further four years from 2019 but with a significant amendment to the method used for electricity pricing. The renewed agreement is linked to the electricity market price of the Nord Pool spot trading platform, replacing ties to the LME aluminum price in the previous agreement.

Writing in Aluminium Insider earlier this year, Christopher Clemence noted that Iceland’s three smelters paid an average of $24/MWh in 2014 — onethird less than the global average for the aluminum industry. However, he noted, Iceland’s advantage in this respect may be slipping away as Landsvirkjun seeks a better return on its investments in new generating capacity.

As a result, Clemence said, Rio Tinto’s price for power doubled to $30/MWh under the new contract it signed in 2010, and is probably closer to $35/MWh now. Having extended its agreement with Landsvirkjun, Norðurál’s supply contracts with two other generators come up for renewal in the 2020s, with significant increases from the current $20/MWh expected. And to complete the roundup, Alcoa’s power supply contracts for Fjarðaál are due for renegotiation within the next 10 years. The era of cheap Icelandic power for aluminum smelting may be coming to end, Clemence predicted.

And, of course, it is not just aluminum smelting that takes advantage of Iceland’s abundant power. Landsvirkjun is suppling 58 MW of geothermal-sourced electricity to the new PCC SE silicon metal production plant at Bakki, which is scheduled to come on stream next year. Located near Húsavík on Iceland’s northeast coast, the $300 million plant will process quartzite obtained from a PCCowned quarry in Poland into 32,000 mt/y of silicon, most of which will be exported to German consumers.

LKAB Holds Firm

Having posted a substantial loss in 2015,

Sweden’s state-owned iron-ore producer,

LKAB, came close to break-even last

year, eventually showing a SEK1.7 billion

($200 million) operating loss after impairments.

Increased delivery volumes,

improved prices and the effects of its

cost-cutting program made a positive

contribution to the improved result, the

company noted in its annual report.

LKAB’s output of 26.9 million mt of products during 2016 was up from 24.5 million mt the previous year, while its deliveries rose from 24.2 million to 27 million mt. It also reported that it had achieved a record 84% of its sales as pellets in 2016, reflecting its drive toward marketing higher-value products. In October, it carried out blast-furnace tests on 300,000 mt of a new pellet product for the European market that it had produced at Malmberget.

At the end of the year, the company also announced that it has mothballed its Mertainen open pit — one of three in the Svappavaara district. The decision to develop the mine was taken in 2010 when the price for coarse iron ore fines was high, with Mertainen seen as a good source for this type of product.

“The market has changed in recent years,” explained Moström at the time. “We are therefore focusing on the Leveäniemi and Gruvberget open pits at Svappavaara and leaving Mertainen dormant until the market conditions change.

“The facilities at Mertainen will be kept in a condition such that we are able to start production at just a few months’ notice,” he added. “We are thus ready for any change in the demand for coarse fines.”

Crude ore production rose at each of the company’s production centers, reaching 26.9 million mt at Kiruna, 16.4 million mt at Malmberget and 6.1 million mt at Svappavaara. LKAB is changing the focus for its exploration from looking for new surface deposits to obtaining better long-term knowledge of its underground resources, such that exploration drilling at Malmberget increased from 50,000 m in 2015 to 85,000 m last year.

In its quest for new markets for its products, in June LKAB announced the formation of a new joint venture company with the Swedish steelmaker, SSAB, and the power generator Vattenfall, to progress the Hybrit fossil-free steel-production concept. This aims to replace existing coal- and coke-fired blast-furnace technology with a hydrogen-based process that would emit water rather than carbon dioxide.

“The joint-venture company will enable us to work together effectively to eliminate the root cause of carbon dioxide emissions in the steel industry,” said Martin Lindqvist, president and CEO of SSAB. Moström added, “It indicates our conviction that it is possible to develop a fossil-free production chain all the way from mine to steelworks.”

Hydro’s New Technology

In August, Norwegian aluminum producer,

Hydro, officially opened its new technology

pilot plant, designed to test what

the company claims is “the world’s most

climate- and energy-efficient technology

for aluminum electrolysis.” Having cost

NOK4.3 billion ($520 million) to build,

the 75,000-mt/y plant at Karmøy, near

Stavanger on the country’s southwest

coast, is scheduled to begin production

late this year.

According to Hydro, the aim of the new HAL4e technology is to reduce energy consumption by around 15% per kilogram of aluminum produced in relation to the international average, and with the lowest CO2 emissions in the world. “What we are building now is a high-tech pilot for the future, with the world’s most energy- and climate-efficient aluminum production,” said Hydro CEO Svein Richard Brandtzæg.

“The pilot will show the way not only for Karmøy, but for all our plants in Norway and around the world. So this is a pilot for all of Hydro, for the growth of future-orientated industry here in Norway, and for the global climate,” he went on. “The technology pilot here at Karmøy is green, smart and innovative,” said Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg, who performed the opening ceremony.

For 2016, Hydro reported the production of nearly 2.1 million mt of primary aluminum, with record production of bauxite (11.1 million mt) and alumina (6.3 million mt) from its Paragominas mine and Alunorte refinery in Brazil. Last December, the company paid Vale $113 million for its residual holding in Mineração Paragominas, thereby achieving full ownership of the operation. Hydro reported net income of NOK6.96 billion ($850 million) for 2016, up from NOK2.3 billion in 2015, although the average price realized for its aluminum fell from $1,737/mt to $1,574/mt year-on-year.

In July, Hydro agreed to buy Orkla’s 50% share in the Sapa joint venture, formed in 2013 when the two companies combined their aluminum extrusion assets. Hydro believes the acquisition will make it the only global company in the aluminum industry that is fully integrated across the value chain and markets. Valued for the transaction at NOK27 billion ($3.4 billion), Sapa is the world’s leading supplier of extrusion-based aluminum products, with a 22% market share in Europe and 24% of the North American market.

LNS then formed Greenland Ruby as the new license-holder for Aappaluttoq, also being responsible for marketing the mine’s output of rubies and pink sapphire — both types of corundum. The hard-rock deposit is hosted in an Archean anorthosite complex consisting of multiple layers of mafic to ultramafic rocks. According to True North Gems, corundum found in micaceous primary ore is relatively easy to extract, whereas secondary gabbroic ore is harder, making the recovery of unbroken stones more difficult. Around 5% of the corundum is high-end gem grade, a further 20% is “near-gem,” and the remainder is “commercial” quality.

Speaking at the official opening of the mine, LNS CEO Gunnar Moe said, “We are extremely proud to be the first commercial gemstone mining operation in Greenland, and look forward to entering the marketplace with ruby material that can match that from traditional sources such as Burma, Thailand or recent findings in Mozambique.”

Recovery of the gem material involves initial crushing, followed by scrubbing, some hand sorting, re-crushing oversize, dense-medium separation and optical sorting. Final cleaning with hydrofluoric acid results in a concentrate that is sent to the company’s sorting house in Nuuk for grading and subsequent marketing.

... and Maybe From Finland?

In August, one of the junior companies

exploring for diamonds in Finland, Karelian

Diamond Resources, published the

results of a preliminary economic assessment

on its Lahtojoki kimberlite pipe in

southeastern Finland. The study suggests

that capex of $22 million would be needed

to develop an open-pit operation there,

with the potential for producing more

than 2 million carats (ct) of diamonds

over a nine-year life. As the company

pointed out, this would be the first European

diamond mine outside Russia.

Drilling has indicated an inferred resource of 5.6 million mt to a depth of 160 m, containing a non-JORC estimate of 2.225 million ct. Chairman of Karelian Richard Conroy said, “Clearly much work remains to be done, but this report is a major and very encouraging step forward in our assessment of the Lahtojoki diamond project and of its potential for development as a mine.”

Karelian is only one of several companies that have looked at Finland’s diamond potential in recent years. One of the earliest, the local copper-mining company Malmikaivos Oy, began work in the 1980s together with Australia’s Ashton Mining, while European Diamonds (a forerunner of today’s Firestone Diamonds with operations in Lesotho and Botswana) discovered the White Wolf and Black Wolf kimberlites in northern Finland in 2005.

These are now included in Arctic Star Exploration’s Timantti project, where in July the company announced the recovery of 111 micro-diamonds from 48.65 kg of material obtained from the Finnish Geological Survey’s (GTK) core store.

Around the Mines

in Finland ...

In August 2015, the Finnish state company

Terrafame acquired the Sotkamo

mine and heap-leaching operation from

the bankruptcy administrators of Talvivaara

Sotkamo Ltd. The company is

now aiming to mine and leach 18 million

mt/y of ore with a 70% minimum target

leaching yield.

During 2016, the operation ramped

up capacity, and by year-end had

produced 9,554 mt of nickel and

22,575 mt of zinc, plus cobalt and copper,

from 14.2 million mt of ore. Capex

during the year totaled €84.3 million,

with the operation posting an EBITDA

loss of €120.4 million ($130 million).

A second metal production circuit was commissioned in October, with around 75% of the primary bioleaching area being in use by the end of 2016. Major investment was made in constructing two secondary bioleaching pads, and in a centralized water-treatment plant, which entered trial use in November. Water management has been a critical aspect of the Sotkamo operation since its outset, with the company achieving a significant reduction in the volume of water held onsite during the year.

In February, the state holding in Terrafame was effectively reduced by 15.5% under a €250 million funding agreement with Trafigura and its private investment arm, Galena Private Equity Resources Fund. The agreement also committed Trafigura to buy all of the mine’s nickel production and 80% of its zinc output for the next seven years. Capex needed to complete the reconstruction of the operation is estimated at €150-200 million.

Agnico Eagle’s Kittila gold mine in northern Finland produced 202,500 oz from 1.6 million mt of ore in 2016, with the company predicting production at similar levels for the next three years. The cash production cost was $699/oz.

Agnico Eagle is now studying the potential for expansion to 2 million mt/y, with a $7.9 million exploration budget for 2017 that is aimed at expanding the mineral resources in the Northern part of the property and demonstrating the economic potential of the Sisar zone. Kittila is the largest primary gold producer in Europe and hosts the company’s largest mineral reserves.

... in Sweden ...

Meanwhile in Sweden, Agnico Eagle

has a 55% interest in the Barsele gold

prospect, where inferred mineral resources

are estimated to be 21.7 million mt

grading 1.72 g/mt of gold, containing

1.2 million oz. The company has reported

that the deposit appears to have bulk

tonnage and underground potential.

Agnico Eagle can increase its holding to

70% by completing a prefeasibility study

on the property, which, it said, appears to

be geologically similar to its Goldex deposit

in Québec.

Since 2015, Lundin Mining has been working on a project to increase plant capacity at Zinkgruvan in central Sweden by 10%, with successful commissioning achieved earlier this year. The company has also been increasing the capacity of the mine’s tailings dam. The embankment reached its final height last November, and the first phase of the new dam should be completed shortly.

The mine produced 78,500 mt of zinc during the year, 31,600 mt of lead and just 1,900 mt of copper. No copper ore was processed for much of the year, with the company maximizing plant capacity for higher-value zinc-lead ore. Lundin reported that current reserves are sufficient to support mining for at least another 10 years.

At the end of last year, Boliden published updated reserve estimates that provide an indication of the potential residual lifespans of its operations. Garpenberg in Sweden currently tops the list at 29 years, two years longer than Aitik, although the company plans to seek permitting for mining at the nearby Nautenen deposit there this year. The Boliden area has a further seven years of production at current rates unless new resources are identified.

At its Finnish operations, Boliden estimated that Kevitsa, recently acquired from First Quantum Minerals, currently has 16 remaining years at full production, but that Kylylahti is likely to be exhausted by 2019. The company noted that it is prioritizing its exploration within existing mining areas.

Boliden reported mine production of 329,000 mt of zinc during 2016, 103,000 mt of copper, 63,000 mt of lead, 7,000 mt of nickel in the second half of the year, 5,766 kg of gold, 446,800 kg of silver and 38,680 kg of tellurium. Smelter output was zinc, 461,000 mt; copper, 336,000 mt; lead, 74,000 mt; nickel in matte, 31,000 mt; gold, 17,638 kg; and silver, 609,100 kg; plus 1.6 million mt of sulphuric acid.

With mining completed at Svartliden in 2013, the company has maintained use of the plant there in anticipation of receiving test mining permits for the nearby Fäboliden gold deposit, where the previous owner, Lappland Goldminers, had completed a feasibility study on an open-pit operation. In the meantime, it has been processing concentrates from Vammala, but during 2016 stopped taking external concentrates containing high leachable copper values because of the potential effect on water discharges.

Aside from Fäboliden, Dragon Mining is working on bringing its Kaapelinkulma project in southern Finland into production, with commissioning of the open-pit operation scheduled for early 2018. The company produced 34,400 oz of gold from its Nordic operations during 2016.

... and in Russia

Across the border in Russia’s Kola

Peninsula, Kola MMC (part of the

Nornickel group) operates a number

of open-pit and underground coppernickel

mines, with two smelters at

Zapolyarny and Nikel. While sulphur

dioxide emissions from the plants

have been a long-standing issue in

both Norway and Finland, The Barents

Independent Observer recently reported

that changes to the processing

system at Zapolyarny, replacing roasting

with briquetting, has cut emissions

there substantially.

Against this achievement, SO2 emissions from the Nikel plant have risen but are now being captured to a greater extent as feedstock for the smelter’s revamped sulphuric acid plant. With plans for two new mines, the 1-million-mt/y Sputnik open pit and the 1.5-million-mt/y Yuzhny underground mine, to be on stream by 2018, Kola MMC is spending RUB27 million ($500,000) on upgrading its rail and logistics systems at its Monchegorsk nickel refinery.