The Cripple Creek & Victor operation in Colorado is investing in a new valley leach facility (seen here) and a new plant.

Newmont Repositions and Reaps the

Rewards

The leading U.S. gold producer shares some of its secrets for finding the full potential

of its mines and projects

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

Similar to most of the miners in the gold space, Newmont Mining Corp. was reviewing its portfolio as the gold price began to plummet in late 2012. How they managed through that period is what sets them apart from other gold producers today. Making some difficult decisions, they created a solid foundation from which they began to build.

Since mid-2013, the company sold several assets totaling nearly $1.9 billion. This move allowed them to pay down debt and invest in new, profitable production. At the same time, Newmont was optimizing operations by looking at each asset’s full potential and improving operating costs and efficiency. They were in effect learning to live within their means again, which meant being able to operate profitably with gold prices in the $1,000- $1,100/ounce range. Newmont cut capital and exploration budgets, yet they were still delivering new projects and adding reserves. During this period, it should be noted that the company never flinched on its commitment to safety or sustainability.

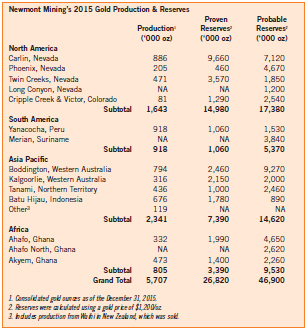

As of mid-2016, Newmont has lowered net debt by 49% since 2013, reduced its all-in sustaining costs (AISC) by 28% since 2012, and delivered positive free cash flow for eight of the last nine quarters. An opportunity presented itself in 2015 and the company purchased the historic Cripple Creek & Victor (CC&V) mine in Colorado from AngloGold Ashanti. Today, Newmont is advancing five development projects, which are expected to generate an additional 1 million ounces per year (oz/y) of gold production at AISC of $700/oz over the next two years. On top of that, the company added 13.4 million oz of gold reserves by the drill bit in the last three years.

Just before the downturn, Newmont brought Gary Goldberg on as COO in 2011. A mining executive with an engineering background, he had spent 35 years working in many different roles with Rio Tinto and Kennecott. Knowing the company needed a change, Newmont’s board promoted Goldberg to CEO, and working together they began to chart a new strategy. This wasn’t the first time in his career that he had seen the market soften, but he needed to answer that burning question: What are we going to do?

The strategy the company devised was fairly simple, Goldberg explained. “First we would improve the underlying business,” Goldberg said. “Then we would shape the portfolio properly so that we could deliver value to shareholders. With that, we had to make sure we had the right capabilities within the business. One area where we have strengthened the business is in our technical competence.” Newmont had a good base, but with gold being so variable, understanding the ore bodies and the risks associated with them was critical.

The current leadership team is a mix of Newmont executives and other executives with whom Goldberg has worked in the past. When Goldberg was appointed COO, he split the Batu Hijau operation in Indonesia out as a fifth division. They brought mining veteran Tom Palmer on board and for a year he had Batu Hijau directly and, when it was merged back into Newmont’s Australian-Pacific division, Palmer became a senior vice president for the region. Palmer was named executive vice president and COO earlier this year when Chris Robison announced his plans to retire after a 36-year career. Prior to joining Newmont, Robison was the COO at Rio Tinto Minerals under Goldberg. He and Goldberg’s relationship extended all the way back to their early days at Bingham Canyon in Utah in the 1980s.

While the operations strategy was being revised, Goldberg also challenged his exploration team’s views on orebodies, asking them to look for additional mineralization near existing operations. Grigore Simon, the senior vice president for exploration, leads Newmont’s global exploration program. With a similar objective, he and his team are focused on delivering the best margin ounces rather than just adding any ounces.

Over the last few years, the Newmont leadership team has made a lot of changes. “We no longer have a huge growth focus,” Goldberg said. “We have a fit-forpurpose organization that produced as much gold last year as it did three years ago with 27% fewer people, while dramatically improving the company’s safety performance.” He attributes the company’s success to building leaders rather than training managers.

Safety as a Core Value

Goldberg places a high value on safety and

he expects the same from everyone else in

the organization. “You’re never quite there

as far as safety performance,” Goldberg

said. “We led quite an effort to improve

our performance. The results are visible,

but we have not reached the level where

we need to be. We had two fatalities last

year. This year, we have made significant

inroads—no fatalities nor serious injuries.”

Goldberg was involved with a group of mining CEOs who launched the National Mining Association’s CORESafety Program and he said he is still impressed with the program. “When you look at the stats of the companies that decided to use those tools, their safety records have shown noticeable improvement,” he added.

Palmer echoed those sentiments. “When it comes to safety, fundamentally the approach we are taking is that safety is a core value rather than a priority,” Palmer said. “Priorities can change. People could put themselves in position to choose something else, such as production, over safety. We talk about safety as value because it’s constant and comes before other things and remains a foundation.”

Newmont has experienced some success bringing injury rates down. In fact, they are down more than 50% over the last three years. “More importantly, the severity level of the incidents has also declined significantly,” Palmer said. “We maintain a chronic unease about things we still need to do to improve and maintain safety performance.”

The company is currently focusing on three key areas: fatality risk management; the rigor and discipline to investigate and apply lessons learned; and visible leadership. “Ideally, a great fatality risk management program adopts and applies best practices globally and shares it with others in the industry,” Palmer said. “To build that program, everyone from the frontline manager to the miners has to own it.” A key part of a well-designed fatality risk management program is understanding the critical controls that need to be in place to prevent a fatal injury from occurring, Palmer explained.

Addressing rigor and discipline, Palmer explained that, even if no one was hurt during a significant event, the group has to conduct a quality investigation to extract the lessons learned from it and then share those lessons. “Sharing the story is important and controls must be implemented to prevent it from happening again,” Palmer said. “As far as visible leadership, we have leaders at all levels engaging with their teams on ways to improve on safety, whether that’s a pat on the back to encourage good behavior or coaching as to how to perform a task more safely. A safe company needs a visible presence of leadership in the field.”

“Today, more people at Newmont are going home safely every day and that’s critically important to me,” Goldberg said. “This has always been an indicator of what is working well. If safety is not going well, usually the other parts of the operation are not working well either.”

Hitting the Ground Running

In addition to safety, what attracted Goldberg

to Newmont was its reputation as far

as operational performance. After joining

the company, toward the end of 2011,

gold reached its modern day peak in nominal

terms. “Yes, and then it started to go

the other way, which is not inconsistent

with what I have seen working with a number

of other commodities,” Goldberg said

with a chuckle. His career includes stints

with copper, gold (with another company),

coal and industrial minerals. This time was

a little different though: the gold industry

had gone 12 years without a downturn.

“We had half a generation who had not seen a downturn,” Goldberg said. “To help the business, we needed to put a process in place to make sustainable improvements in costs and efficiency. Anyone can cut costs to get by in the short term, but that does not improve the underlying business.

“During that period, metal prices increased and so did operating costs,” Goldberg said. “Some of those were due to uncontrollable forces. There was a big focus on growth and sometimes growth at any cost. People felt prices would continue to climb. So changing the culture from a volume-focus to a value-focus was the other critical piece to the puzzle at that time.”

Goldberg had a year as COO to see the operations and determine what was working. He had a chance to put a few plans in place in terms of the rigor as to how capital decisions were made. “That was a big factor as far as taking the lessons we have learned from the past—what has worked well and what hasn’t—and applying that experience to investment decisions so that we continue to improve our decision-making ability,” he said.

The results materialized with eight recent projects that have been completed or are in the process of being completed on time or sooner and at or under budget. “That doesn’t happen much in the mining business these days,” Goldberg said. “We invested in projects during the downturn using our free cash flow,” he said. “No one else was really doing that in the gold space. Overall, development capital for the mining business is down 80% over the course of the last five years. And, that’s offered us some opportunities.”

As an example, Newmont’s Merian project in Suriname, which will be commissioned later this year, is so far $100 million below budget and it will be a little ahead as far as timing, Goldberg explained. “Less competition for construction talent and less competition for mining and mineral processing equipment opened opportunities to be more cost effective,” Goldberg explained. Another example of the improvement efforts was a focus on ore body risk.

Underpinning overall business improvement efforts is a program called Full Potential. Regional leaders and technical staff began to evaluate each operation and chart a course to significantly improve costs, efficiency and technical fundamentals. They also enlisted a consultant to help measure performance consistently against benchmarks and track it appropriately moving forward. “It wasn’t us telling the sites what to do,” Goldberg said. “It was the sites developing ideas that they knew would improve performance, and owning the process of realizing those improvements. We weren’t asking for three- to five-year plans. We asked them what they could deliver within the next year. Then we reviewed what we had accomplished and decided what should be built into the plans for next year.”

There was a degree of conservatism included in those plans as far as gold prices, Goldberg explained. “We built cost escalation into the programs and they had to make adjustments,” Goldberg said. As far as results, Newmont has posted a 28% reduction in AISC over the last three years.

Making Difficult Decisions

Shortly after Goldberg was named CEO,

Newmont sold the Midas operation for

$83 million. Then in 2014, after an odd

dance with Barrick Gold, it sold Jundee

for $91 million and its stake in Penmont

for $477 million. Cash flow began

to improve in 2014 and in 2015, they

announced plans to build Long Canyon

Phase I in Nevada and expand production

at Tanami in Australia, and completed

the acquisition of CC&V. In 2015,

the company sold the Waihi operation in

New Zealand for $101 million before announcing

it plans to sell Batu Hijau for

$920 million in June.

Deciding what to keep and what might be more valuable to someone else is never an easy decision. “We look at all of our operating assets and projects using the same value versus risk matrix,” Goldberg said. “For value, we look at net present Value (NPV), rate of return, position on the cost curve, and mine life. As far as risk, we look at the social and political risk, and technical risk.”

Once those parameters have been identified, leadership decides what it would take to move these projects in a direction that would be more desirable, e.g., lower risk and higher value.

Offering the Tanami operation in Australia as an example, Goldberg explained that Newmont had a mine producing gold at $1,600/oz in 2013. With no research, one could easily conclude that this would be a property the company would want to unload. “And, we were considering that,” Goldberg said. “However, we made some changes to the leadership and changes to how they were executing the mining plan. They were not keeping up with the backfill that was needed. If you get too far behind, you’re mining where you shouldn’t be. They were also behind on development work. So, we pressed the reset button.” Today, Tanami produces gold at an AISC of $800/oz and Newmont has one of its better incremental projects. A second decline and plant expansion were approved earlier this year to increase profitable production and mine life at Tanami.

Goldberg explained that Midas was a better fit for the buyer because the mill was of more value to them. With Jundee, it came down to how far they could take the resource with narrow-vein mining and the mill. They thought they could leverage the regional mining experience at Waihi with an upside on the exploration side. “We kept a royalty interest in place,” Goldberg said. “The companies that purchased these assets were all good companies and we were comfortable with the sales arrangements.”

The sale of its interest in Penmont, which operated Mina La Herradura, one of the largest open-pit gold mines in Mexico, to Fresnillo was another example of a better fit for the buyer. “The mine was moving from open-pit mining operations to underground mining and it would be free cash flow negative for a five-year period,” Goldberg said. “Fresnillo was interested in buying our interest in the operation and we crafted a transaction that made sense for both parties.”

Newmont also sold some noncore assets, the first being an interest in Canadian oil sands in the middle of 2013. “It’s not that we knew the price of oil was going to drop precipitously. Timing is everything,” Goldberg chuckles. “Sometimes you just get lucky and we got lucky on that deal.”

Similar to much of the mining sector, Newmont had been taking on debt to fund growth prior to 2012. Now it needed to get the debt position back into a more comfortable spot. “We used the proceeds from these sales to do that,” Goldberg said. “By getting costs down, we were generating positive free cash flow, which we used to reduce debt and invest in our most promising projects.”

Then the opportunity with CC&V presented itself. “We participated in a process and looked it over,” Goldberg said. “It’s in an area that we understand, working in the U.S. We thought we could bring additional value to the operation. Anglo needed to sell because they needed the cash and it worked out in terms of timing. A year earlier, we probably would not have been able to acquire the property because we simply didn’t have the cash position.” Newmont targeted 10% improvement in mining costs for CC&V and is on track to realize this target and to deliver even more improvement in 2017.

In June, Newmont announced its plans to sell its Batu Hijau operation in Indonesia. Goldberg doesn’t view this transaction as Newmont exiting copper. He sees it as an exit from an asset. “Newmont had great success with Batu Hijau over the years,” Goldberg said. “We run it with 6,000 employees and contractors and only a dozen or so are expats, so it’s pretty much run by Indonesians. The country is pursuing in-country processing and smelting. While we support their direction, given the nature of the orebody, we could not justify an investment in smelting capacity.”

The Batu Hijau orebody is mined in phases, with a stripping phase followed by an ore mining phase. Currently, the operation is halfway through Phase 6 ore mining. “It will soon face five years of stripping before it reaches the Phase 7 ore,” Goldberg said. “It would cost another $2 billion to get there. The sale of Batu Hijau was an investment decision. We have been working with the people who are buying the operation for about a year now and we still have a lot of work to do to maintain a smooth transition.”

Bringing 5 New Projects Online

Newmont has five new projects in the

pipeline, which will add 1 million oz of

gold production in the next two years.

These include Long Canyon Phase I in

Nevada, the new Merian mine in Suriname,

a second decline and plant expansion

at Tanami, a new mill, leach pad and recovery

plant at CC&V in Colorado, and an

underground expansion called Northwest

Exodus in Nevada. These five projects met

the rigorous conditions that had been set

as far as improving value for the company.

The plan for Long Canyon was modified during the evaluation process. Initially, it was a $500 million project that included a mill and some new equipment, yet it only had a six- or seven-year mine life, Goldberg explained. “We challenged the team, saying that we only wanted to invest in what was needed for Phase I,” he said. “So we removed the mill and went with used equipment. The project cost is now estimated to be between $250 and $300 million. That’s a substantial reduction in upfront capital, which allowed the project to clear economic hurdles in a low price environment.” With gold selling in the $1,200/oz range, Long Canyon Phase I has a rate of return in the high teens.

With Merian, Goldberg mentioned that he has given 10-year service awards to people in Suriname. “We have been there a long time exploring and working to develop the potential resource,” Goldberg said. “The key to us was getting the mineral agreement with the government to be able to develop the property and working with a different model to build it.”

Rather than bringing in the typical EPCM contractor, Newmont opted to work with G Mining Services, which is owned by Louis Gignac, an ex-Cambior miner that has built other facilities of this size elsewhere in the world including Suriname. “They have really good experience building projects and I have been working with Louis for a long time,” Goldberg said. “He and his team, which includes his sons, do great work. So far, we have saved $100 million, part of that is due to G Mining and part of it was the less-competitive environment.” The Merian mine will produce, on average, 450,000 to 500,000 oz/y at AISC of between $650/oz and $700/oz in the first five years of production, and will achieve commercial production in the fourth quarter of 2016.

Goldberg also noted that the government of Suriname is a partner in this project. “They paid for their 25% share and they have been making capital contributions along the way,” Goldberg said. “Oftentimes, when a government is a partner in a major mining project, it’s a free carried partner by the asset’s owner. In this case, they are like another equity owner and they have paid their fair share.”

The CC&V operation is investing in a new mill, valley leach facility and recovery plant. “The mill was experiencing some commissioning issues, primarily with the filter presses, when we took over,” Goldberg said. “We have now cracked that nut as far as the throughput issues we inherited. We commissioned a new pad at the leach facility and we will be commissioning a new recovery plant in the next few months.”

Northwest Exodus is an extension of the current operations in the Exodus mine, down dip further to the northwest. “We just approved this project, which is estimated at $50 to $75 million to finish the development work around the deposit,” Goldberg said. “One of the things the people in Nevada do really well, especially the people at Newmont, is declines off the open pit into an underground mining operation. We will have to install a raise and some ventilation equipment and that will be completed mid-2017. We will be in full production by 2018.” This is a natural extension of an existing orebody, which speaks volumes about exploration as a core competency.

Capital Deployment and Cost Cutting

Palmer’s career has taken him through a

bunch of different commodities. Although

gold holds a distinct standing in the mining

business, Palmer explained, the operational

principles applied to mining are

universal. These include: effective leadership,

strong technical fundamentals and

a culture of continuous improvement.

“There is a significant amount of overlap

between all three areas,” Palmer said.

Palmer believes that once an organization has that basic foundation in place, or operational credibility, it earns the right to grow. “We positioned ourselves to invest during the downturn,” Palmer said. “We apply the same rigor to our growth projects as we do to existing operations. Whether it’s a new mine or an expansion, it’s all about ensuring that we are taking a fit-for-purpose approach, that we have the fundamentals right and that we are living within our means.”

Can the team deliver on the project it is undertaking? “If a team can keep that question at the forefront of their minds during those investment decisions, then they condition themselves to deliver on schedule and on budget,” Palmer said.

Walking through the current projects, Palmer describes a fit-for-purpose approach. With Merian, Newmont partnered with a contractor who had experience in that region and with the government. “With Long Canyon, we are taking a phased approach in terms of living within our means,” Palmer said. “We decided to go with heap leach vs. a mill and refurbished equipment vs. new. We are also leveraging existing staff and infrastructure in Nevada.

In contrast, using the same metrics for the Ahafo operation in Ghana, Newmont decided to delay a major mill expansion. “Instead, we will take advantage of an expansion of the Subika underground mine,” Palmer said. These are just a few examples of Newmont’s fit-for-purpose approach and living within its means, Palmer explained, which leads to executing on schedule and on budget.

Cost control, according to Palmer, also requires discipline—the discipline to control what can be controlled. “We have to be clear with ourselves as to what we can control irrespective of gold prices,” Palmer said. “About two-thirds of the cost and efficiency improvements we have achieved since 2012—measured as a 28% decrease in AISC on a portfolio basis—are greatly the result of our Full Potential program.”

The program sets clear targets and provides support for operations to assess improvement opportunities while being clear about the accountability. The responsibility for identifying and delivering those improvements lies with the teams. This program continues to deliver value and the operations are setting new targets and reporting how they will achieve them.

Palmer attributes some of the success to technological improvements, which he believes will play a greater role in the future. “There are developments with semiautonomous equipment that can deliver safety and efficiency improvements in certain applications, but greater company- wide benefits will come from the integration of information technology (IT) with operations technology (OT),” Palmer said. “There are clear opportunities to look at data on the IT side, determine trends and make decisions based on OT. As an example, using sensors in haul truck tires, we can link the information to the dispatch center and they can make the decision to either park the truck or keep it running and continue to monitor the situation. The IT/OT integration opportunities with equipment in the pit and plants will allow us to be more proactive especially when it comes to maintenance.”

Another area Palmer considers important are the global metrics or having a common definition of how productivity is measured company-wide. Whether it is truck fleets, mills, excavators, etc., management teams around the globe need to be able to compare operations and share the results when they see something working well. “It’s O.K. to copy success within an organization,” Palmer said.

Looking at the longer term, Palmer said that Newmont has positioned itself to outperform as the market improves. “Likewise, we have the discipline to manage if the market deteriorates,” Palmer said. “We have a solid operational foundation supported by projects and exploration programs that offers opportunities and the ability to bring new, profitable ounces online.”

Adding Ounces by the Bit

There is an old adage in the exploration

business that says the best place to look

for gold is near an existing gold mine. The

executive who leads Newmont’s gold exploration

program, Grigore Simon, said there

is a lot of merit to that expression, but he

also cautioned that there is a catch to it as

well. “The merit is that if you are next door

to an ore deposit in a well-endowed mineral

district, most of the geological risk in

terms of mineralization at the district level

has been eliminated,” Simon said. “The

other significant risk, the economic risk,

is also reduced due to access to existing

infrastructure. So, all you are left with is

the target-specific geological risk.”

Newmont refers to these exploration programs as wingspan or brownfields programs. “With wingspan programs, you have one foot in the ore and with the other one you are trying to figure out if you’re still in the ore,” Simon said. “A brownfield is anything within trucking distance to existing infrastructure. In either of these cases, the odds are in favor of making a discovery.”

The “catch,” Simon explained, is that exploring near existing mines is a short-term fix. “To sustain current gold production levels as an industry for the long-term, significant new greenfield discoveries need to be made, preferably in new geological domains,” he said.

Newmont’s exploration strategy has changed significantly since the downturn in 2012. “We have moved from a focus on volume, which was really intended to maximize the reserve and resource ounce delivery, to a focus on just-in-time and highest margin ounces to support operations,” Simon said. “This translated into a concerted effort to convert the most valuable ounces to reserves and resources as well as a shift toward wingspan and brownfield programs. Despite this focus on near-mine programs, we still maintain a core greenfields program representing about 12% of the exploration budget, which is primarily focused on Nevada, Guiana Shield and the Andes.”

As far as recent major discoveries, the Auron orebody, a brownfield discovery at Tanami, is already in production. “We recently discovered three other blind orebodies at Tanami: Federation, Liberator and Auron West,” Simon said. “This has happened in the last two years. They are all Paleoproterozoic orogenic deposits similar to Callie. This is really important because they are approaching 5 million oz of reserves and resources and we are nowhere near complete with the exploration.”

In Nevada, Newmont has made a number of new discoveries at Northwest Exodus and Exodus Footwall. “These are sediment-hosted micro gold deposits, also known as Carlin-style deposits,” Simon said. “These discoveries just received the go-ahead for development. At Long Canyon, we have made two new discoveries in the northeast zone as well as, the eastern zone, which is less than a year old. We have also had significant success at Rita K-Pete Bajo, southeast of Leeville.”

Newmont has made a number of brownfield discoveries at the Subika underground operation in Ghana and Apensu Deeps. “We also have a new discovery that is just a few months old at Apensu North,” Simon said. “At Yanacocha in Peru, Newmont also has a recent discovery, Quecher Main, that is being moved into development.”

“The shift into brownfield exploration has really started to show some results,” Simon said. “At the same time, we are keeping an eye on greenfield programs. Merian and Maraba are examples of successful greenfield development. They are typical sediment-hosted orogenic gold deposits that are currently approaching 8 million oz of reserves and resources. The Sabajo discovery in Suriname, which is a shear zone orogenic style discovery, is located about 40 km to the west of Merian. And, we have another new copper-gold discovery, which will remain nameless for now.”

What makes this more remarkable is that Newmont reduced the exploration budget by 60% to about $190 million in 2013 and it remains at that level today. “In 2016, 80% of the budget is for nearmine exploration and it is equally distributed between reserves, resources and new discoveries in the near-mine environment,” Simon said. “The remaining 20% is distributed between the greenfield program (12%) and technical support and the technology group. Despite the reduction, we still managed to add 5 million oz of reserves by the drill bit in 2015.”

Historically, Newmont always has had a strong organic new discovery program. Over the last 30 years, Newmont’s exploration group has added more than 200 million oz reserves organically, which more than offset depletion of 150 million oz at a unit cost of discovery of $12/oz, according to Simon. “In the past 15 years, the addition of organic reserves were 123 million oz at a unit cost of $23/oz, which offset 107 million oz of depletion,” Simon said. “About 70% of the ounces we produced last year came from Newmont discoveries. This is due to the talent and dedication of our exploration and R&D team.”

For the near-mine environment, all of the exploration work is performed internally. “That covers reserve conversion, resource conversion and new discoveries around existing mines,” Simon said. “With the greenfield program, it’s a mixed effort. We have a strong collaboration with junior explorers through both operated and non-operated joint ventures and we spend about half of our greenfield budget on these joint ventures. The remainder is invested internally, which goes toward area selection and screening, and target generation. Greenfield exploration is a healthy combination of internal programs and partnerships with junior explorers.”

The technology used for exploration is where Newmont has a tactical advantage. The company has a long track record of technological innovation that started with ground-based Induced Polarization (IP) and ground and airborne Electromagnetic (EM) geophysical methods starting in the 1940s through the 1980s. They also developed a number of geochemical methods through the acquisition of Normandy, the most well-known of which is the bulk leach extracted gold (BLEG) process.

“More recently, through our R&D efforts, we are maintaining a leading edge in electrical methods with the development of the, proprietary airborne NEWTEM system, which stands for Newmont’s time domain electromagnetic platform, and the ground-based IP distributed acquisition system, NEWDAS, which is a 3-D distributed acquisition platform similar to the 3-D seismic systems used in the oil industry that has a depth of investigation of 800 meters,” Simon said. “We have also developed a new proprietary method, deep-sensing geochemistry (DSG), which uses geochemical methods on the surface to investigate to a depth of more than 500 meters through many types of cover.

“We believe that combining these technologies constitutes an unequalled competitive advantage for deep cover exploration,” Simon said. “We use BLEG to screen very large areas and focus exploration efforts very quickly. Then we use the NEWTEM and NEWDAS methods along with DSG to delineate the targets. The BLEG program is credited with discovering Batu Hijau. The size of Ahafo North and the underground sulfide resources at Yanacocha were enhanced using the NEWDAS systems. The recent discoveries at the Long Canyon East Zone and Rita K—Pete Bajo came through the use of deep-sensing geochemistry.”

The Keys to Success

What are the key elements to Newmont’s

success? “We have a clear strategy based

on five strategic pillars: health and safety,

operational excellence, growth, people,

and sustainability,” Palmer said. “We

have operating people who understand

how we work together. We are building a

strong talent pipeline. We want to develop

leaders, not just managers. Our approach

to sustainability and external relations

has paved the way for us to deliver on our

plans with permits and community agreements.

We hold ourselves accountable

and we link the recognition that people

receive to how well they delivered across

all five of those areas.”

Simon definitely agreed. “You need to have the right people for the job,” he said. “You need to place them in the most prospective parts of the world. You need to give them the right technology and then leadership has to have a clear business discipline. The success with exploration programs is mainly knowing when to move ahead faster or more importantly when to stop a program when it is going nowhere.” The common denominator seems to be the people. One of Newmont’s internal surveys revealed that 89% of the employees understand how their work contributes to the company’s success.

“The potential for our team, building on its success and pursuing innovative approaches to raise our performance to the next level—that’s what gets me excited,” Goldberg said. “This is a fun business. It’s great when the prices go up, but the reality is that we have to keep people focused on controlling what they can control. That has made a big difference.” The people at Newmont quickly repositioned the company and now they are seeing that effort pay dividends.