Harmony CEO Graham Briggs had hoped the company would not have to shut down further shafts after closing

several in early 2010, but in April the company announced permanent closure of three more.

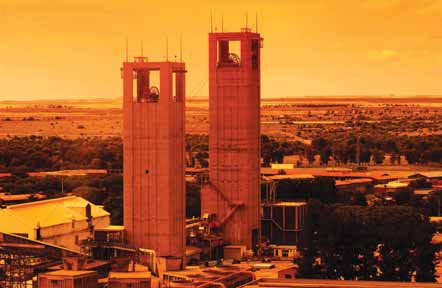

The Decline of South African Gold Mining

Dealing with orebodies past their prime, aging infrastructure and labor issues,

new gold projects in South Africa that will mine even deeper reserves will have to

mine differently for the industry to remain profitable

By Antonio Ruffini, South Africa-based Editor

The decline has come at a time when, in some ways, South Africa’s gold mining industry is in much healthier shape than ever before. It has evolved away from its tainted past by improving accommodation and social infrastructure for workers; the industry has made notable improvements in safety and it is achieving better energy efficiencies.

At another level, however, South Africa’s gold mining industry is distinctly worse off than it was a decade ago. “We are using more workers and achieving less production,” said Vishnu Pillay, who heads up the South African operations of Gold Fields, the country’s second largest gold producer.

Pillay gave three reasons for the decline of South Africa’s gold industry from a Gold Fields perspective. “The overall state of health of the workforce is lower than it was a decade ago,” Pillay said, indicating that HIV/AIDS is having a major impact on the mining industry’s labor force.

“The shafts are old, and we are mining further and further away from the central shaft infrastructure,” Pillay said. “The orebodies are for the most part not in their prime mining phase. In some cases they are already in their tertiary phases, with our South Deep project being the only really new deep level mine the country has seen for some time.”

Harmony Gold Mining Co. Ltd., South Africa’s third largest gold producer, which has operated some of the industry’s more marginal deep level shafts, has closed a number of these over the past few months. At the end of 2009 it closed the Evander Nos. 2, 5 and 7 shafts in South Africa’s Mpumalanga province as well as its Brand No. 3 shaft in the Free State. Harmony CEO Graham Briggs said these shafts accounted for some 100,000 oz of production.

He also said at the time the company would monitor other shafts in the Free State, particularly the Harmony No. 2, and Merriespruit Nos. 1 and 3 shafts in Virginia, as he believed these 60-year-old operations still had potential if they could manage their costs. But by April this year, Harmony decided to close the shafts, with the company announcing those assets have no remaining payable reserves.

But 2009 was no better. Southern Africa Division Vice President Johan Viljoen at AngloGold Ashanti, the country’s largest gold producer, said its South African operations, which produce about 42% of the company’s overall gold, showed a production drop of almost 15% in 2009. This was a decline for South Africa’s largest gold producer of some 300,000 oz to 1.9 million oz from 2.2 million oz in 2008.

Viljoen said that while a major reason for the decline was safety stoppages as applied by the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR), it was not because the company’s safety performance deteriorated— in fact it improved. “Safety stoppages have largely been because of a change in the way the DMR has enforced stoppages on routine visits,” Viljoen said.

As a result of fatalities the government often closed an entire mining complex to investigate the causes of the accident, not just the shafts affected. Like many in the industry, Pillay, who has been in the Gold Fields post for two years, is by necessity diplomatic when asked whether these enforced stoppages are appropriate. “It is my personal goal to run safe operations and ensure the company undertakes no actions and creates no circumstances that can lead to fatalities, injuries or ill health,” Pillay said. “We have made significant progress in reducing fatalities and serious injuries but regrettably we still have had a number of fatalities.

“We have engaged with the DMR on the matter and it is assessing the situation,” Pillay said. “The outcome is already greater flexibility in that now only shafts are being closed after an accident, but only if the Mines Inspector deems the rest of the mine to be safe.”

Gold Fields has already seen electricity costs, which amounted to some R1 billion in its 2009 financial year, increase by 60% to R1.6 billion in the 2010 financial year. With a 25% annual increase in electricity pricing to take place for each of the next three years, this number will go up to over R3 billion a year in 2012.

Gold Fields has already reduced its electricity consumption in South Africa from 610 MW to 550 MW; along with the rest of the mining industry it had to reduce consumption by 10% to help alleviate the electricity crisis that struck in early 2008. Now further energy efficiency measures are being undertaken to contain cost increases and Pillay believes another 10% saving is possible. “In particular we are making sure we put in seals to isolate older working areas and focus our ventilation in areas that we work in,” Pillay said.

Higher productivity at the stope face is also vital. Currently the mine call factor across the Gold Fields South African mines is about 82% and Pillay believes this can be improved. As an industry, South Africa’s gold mines are sometimes accused of worrying more about the tonnages mined as opposed to the gold recovered. Gold Fields provides bonus incentives for its workforce on the basis of achieving safety and production targets. But it is adding a third criterion, based on the quality of production.

The company’s drive to improve productivity at the stope face goes much further. Gold Fields is targeting an increase of the monthly face advance rates by an extra meter per month from its current 6 m and 9 m. “We hope to achieve this by ensuring the logistics to supply material to the stopes is in place, such as additional services and people,” Pillay said.

Another initiative is to mechanize all horizontal development. “Our new South Deep project is mechanized and our Free State-located Beatrix mine, which produces over a metric ton of gold a month, has always had a high level of mechanization. Now we are simply introducing some of these concepts to Driefontein and Kloof, with the introduction of single and twin boom rigs,” said Pillay.

Over the past few years Harmony undertook major projects to upgrade its stable of assets, to replace the marginal operations close to the end of their lives. These included a new mine, Elandsrand, and then Phakisa and Doornkop projects.

The US$139 million Elandsrand new mine project achieved its first production in October 2003 and will achieve full production in June 2012. The 3,000-mdeep operation will have a life-of-mine of 23 years and produce 370,000 oz/y of gold. It has an average reserve head grade of 6.46 g/mt giving it 7.95 million oz lifeof- mine. If the new mine project was not embarked upon, the old Elandsrand operation would in all probability be closed by 2012.

The $168 million Doornkop South Reef project entailed development of the Doornkop main shaft to 1,973 m below collar, to access the South reef. The mine, which will achieve a 5.2-g/mt recovered grade, will have a 13-year life-of-mine during which time it will produce about 2.65 million oz of gold.

The $185.5-million Phakisa project produced its first gold in September 2008 and will reach full production in June 2011. This mine will produce just over 250,000 oz of gold a year over a 22-year life-of-mine. It has a high average reserve head grade of 8.31 g/mt (recovered grade 7.91 g/mt).

The Phakisa mine, whose final depth is 2,427 m below collar, has also seen a number of innovations, in particular its rail-veyor system and the use of a modular ice plant. Though teething problems are usually inevitable when introducing a new technology, the rail-veyor stands out as a new low cost tool for the mining sector.

AngloGold Ashanti, which has seven mining operations in South Africa, is planning to spend more than $3 billion on deep level projects in the country which will deliver 18.2 million oz of gold with first production in 2012, increasing to a peak in 2027.

One of these, at the Moab Khotsong mine near the town of Klerksdorp on the border of the North West and Free State provinces, the project known as Zaaiplaats involves the creation of a deep extension of the current orebody. “We have done all the pre-feasibility work, the feasibility study, and the external audit, and we intend to go to the board for approval in June this year,” Viljoen said. This project will eventually reach a production level of 300,000 oz/y and 5.1 million oz of gold over its life. It will extend the life of mine to about 2036.

At AngloGold Ashanti’s Mponeng operation on the West Wits line near the town of Carletonville, straddling the border of Gauteng and North West province, two projects are under way at what is the world’s deepest gold mine. One is the VCR below 120 project, which is an extension of the current mine over three levels, down from 120 level to 127 level. Its deepest level will be just short of 4 km. “First gold from this project will be produced in 2012,” Viljoen said. “The mine will deliver about 220,000 oz/y from the project and it will extend life of mine by about another seven years to 2026.”

Then there is Mponeng’s carbon leader below 120 project which will reach an eventual depth of 4.3 km. “This project will extend the life of the mine to beyond 2040 at 400,000 oz/y, and will cost well in excess of $1 billion,” Viljoen said. This project was due to go to the company’s investment committee for approval in May this year. “Actual mine development will probably start in 2012, and the project will produce its first gold in 2016.”

The challenge is to go deeper at the end of an existing infrastructure which is already extended. “Initially a mine would have been designed for 25 years, then extended to 50 years, and now we are taking the next step beyond that. It is therefore going to be very important in the future to get the infrastructure right, so that we can, with a different design and a different technology, actually mine at that depth.”

The change will include considering how South Africa’s highly labor intensive deep level gold mines can reduce the impact of using people, versus using other methods, to extract gold.

Meanwhile, Pillay said that all the projects related to South Deep, the country’s first modern fully mechanized deep level underground gold mine, are on schedule. Furthermore, that mine is the first in the country to implement a full day production schedule. This sees workers undertaking a working day rotation with seven days on, two days off, seven days on and then five days off.

At its other South African operations, the company is working to implement what Pillay describes as a work shift arrangement. It sees production for six days a week with Sunday off. The aim is to increase time at the ore face by about a month a year, crucial to making these mines cash profitable. A full day week is not possible at the older mines as a day is needed for shaft repair work.

A recent GFMS gold survey puts South Africa at the highest end of the cost scale among gold producers, but the country’s gold mines remain important. In 2009, South Africa’s gold mining industry earned about $6.35 billion in foreign exchange making it the country’s second largest exporter behind platinum group-metals at about $7.6 billion.

South Africa’s gold mining industry is doing its best to respond to the challenges it faces, through increased mechanization, through increasing efficiencies, through high level talks with government, and possibly through mergers and rationalization of assets between the different gold mining companies, as was recently alluded to by Gold Fields CEO Nick Holland.